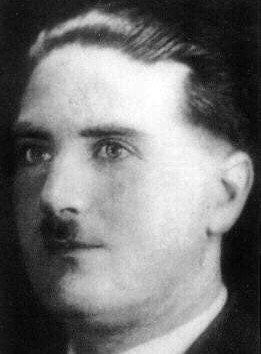

Alfred Arthur Rouse (6 April 1894–10 March 1931) was a British murderer. It was theorised, though never proved, that Rouse, seeking to fabricate his own death, picked up a hitch-hiker, knocked him out, and then burnt his car with the man inside.

His case is unusual in legal history because the identity of the victim was never known and therefore Rouse was convicted of the murder of an unknown man.

Early life

The son of W.E. Rouse, a hosier from Milkwood Road in Herne Hill, Rouse was born in London. His mother was Irish and reported to be an actress. In 1900, his parents' marriage broke up, apparently because his mother deserted, and Rouse and two other children of the marriage were taken to be brought up by his aunt on his father's side. He went to a council school where he was bright (but not exceptionally so) and athletic.

On leaving school Rouse learned carpentry and also went to evening classes where he learned to sing and to play musical instruments (the piano, mandolin, and violin). He had quite considerable musical ability and his voice developed into a good baritone.

He worked first as an office boy for an estate agent, and then in 1909 used his carpentry experience to join a West End furniture manufacturer. A member of the Church of England, Rouse was a sacristan at St Saviour's Church in Stoke Newington.

Wartime service

When war broke out in Europe, Rouse enlisted (8 August 1914), being assigned to the 24th Queen's Territorial Regiment as a Private and assigned the number 2011. The Regiment kept him for training in England before his departure for France, and in the meantime Rouse married Lily May Watkins at St Saviour's Church, St Albans on 29 November.

Rouse arrived in France on 15 March 1915, and was stationed in Paris for some weeks before his unit was sent into battle. During this time, Rouse is known to have fathered a child. His unit was then committed to the Battle of Festubert on the Ypres salient, which began on 15 May. In a bayonet attack, Rouse came face to face with a German soldier and lunged at him but missed; the memory of waiting just for an instant for the enemy reply stayed with him.

On the last day of the battle, a high explosive shell exploded close to Rouse's head, severely injuring him (he also had injuries to his thigh).

Recuperation

An operation had to be performed on Rouse's left temporal region to remove shrapnel, and his leg injuries left him unable to bend his knee, and his leg suffered from an œdema; he could walk, but only with difficulty. He was repatriated and sent to recuperate at a series of Army hospitals. An Invaliding Medical Board hearing on 9 December, 1915 found that his capacity had been "reduced 3/4".

Rouse was formally discharged from the Army on 11 February 1916, and awarded a pension of 20 s per week. His medical records show he was still severely disabled. In July 1916 the doctor noted that Rouse's memory was defective and he was unable to wear a hat of any kind because his scar was irritable, although his speech and writing were unaffected and he "sleeps well unless excited in any way". His pension was raised to 25/- per week the next month.

At the end of January 1917, the doctor found progress, and believed that the injury to his leg could "by degrees be overcome by the man's own endeavour". A year later, Rouse reported some dizziness but the doctor noted how he was talkative and "laughs immoderately at times". September 1918 saw Rouse complain of defective memory and bad sleeping.

Return to work

On 30 July 1919, Rouse was examined again by an unsympathetic doctor who observed that he was now in no disability from his head wound, and that while Rouse wouldn't allow his knee to be flexed by more than 30%, there was no physical reason for the limitation and the doctor ascribed it to neurosis. His pension, which since September 1918 had been 27/6 per week, was cut to 12/- per week on 17 September 1919.

Finally in August 1920 a final examination found his head injury healed, and his knee injury only slightly affecting movement. Rouse's pension stopped on 14 September 1920 with payment of a lump sum of £41 5s. in final settlement of all claims.

In fact Rouse had already found work.

Murder

On the early morning of 6 November 1930 two men in Northamptonshire saw a fire in the distance. A man approaching them from the direction of the fire observed that 'somebody must be lighting a bonfire'. The two men went to investigate and discovered the fire was coming from a vehicle that was ablaze, containing a body charred beyond recognition.

The licence plate identified the car as belonging to an Alfred Arthur Rouse, a north-Londoner. Rouse had gone to Wales to one of his girlfriends, but returned to London a day later. He was arrested and confessed, saying that he had picked up the victim during a ride to Leicester. While Rouse went to urinate, the man lit a cigarette in the car.

According to Rouse, there was a flash of light, and subsequently the car burst in flame. Alfred Rouse stood trial in Northampton in January 1931, and was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death.

On 10 March 1931, he was hanged in Bedford. He confessed to the crime shortly before the execution.

In Alan Moore's novel Voice of the Fire, set in Northampton at various times throughout history, one chapter tells Rouse's story in first-person narrative, an evasive and self-serving musing to himself as he sits in the dock during his murder trial. The chapter ends with Rouse seemingly convinced of his ability to charm his jury into acquitting him, with his judgment in this matter proving as poor as it had been throughout the entire story.

Wikipedia.org