After 12 years on death row and a desperate final legal battle to save him, the wretched life of Nick Ingram ended early today in Georgia's electric chair.

Three hours after an earlier stay of execution was dismissed by a federal appeals court, Ingram, 31, was led into the death chamber at the State Maximum Security Prison here, strapped into the brown wooden chair and electrocuted with more than 2,000 volts passing through his body. Doctors pronounced him dead minutes later.

Born in Britain and holder of dual British and US nationality, Ingram was the 19th person executed in Georgia since the state resumed capital punishment in 1983, and the 272nd since the death penalty was restored by the US in 1976.

He died despite a passionate international effort to save him. British Telecom operators said today they had been "inundated" with calls from people wanting to ring the prison and ask for the electrocution to be halted.

As he prepared to go the electric chair, Ingram was said by prison authorities to be drinking coffee, "quiet and stone-faced". There were two chaplains with him. Six media representatives went into the prison to view the execution

As the tortuous legal battle reached its climax, his attorneys' last hopes rested with the US Supreme Court in Washington to which they, in vain, filed an appeal. Other avenues were closed by the ruling of the 11th Circuit Court of Appeal in Atlanta, which quashed a three-day stay of execution granted earlier in the evening by District Judge Horace Ward.

Judge Ward granted the stay, even though he dismissed pleas by Ingram's lawyers for a new hearing to examine alleged new evidence that he was drugged at his trial in 1983 and unable to brief his defence lawyers.

As the court battle moved into its macabre end game, events at the prison here followed the grisly choreography of Thursday, when Ingram came within an hour of being strapped into the electric chair and killed.

Once again, his family paid their last visits, with his British mother, Ann, describing as "disgusting and barbarbic" the ordeal her son was going through.

Michael Bowers, Georgia's Attorney General, said as he arrived to witness the execution: "It will be a solemn and grim business not to be taken lightly."

He said Ingram's being on the state's death row for 12 years represented a travesty of justice. "Twelve years is long enough. It's way too long. This is way, way too long. This is not justice.

"Think about the victim's wife, who has had to relive this time and time and time again. This case has had over 15 legal reviews . . . someone far smarter than I said that justice delayed is justice denied, and this is a perfect example."

And as the final death watch approached, Georgia's prison department's spokeswoman, Vicki Gavalas, clinically described what seemed to be Ingram's last day on earth; how he ate little breakfast " a few spoonfuls of eggs and grits", how later he had some crackers and chips bought by relatives from a prison vending machine.

Once again, Ms Gavalas, in elegant coiffeur and sporting gold necklace and bangles, smoothly answered questions as if she were describing arrangements for a small-town convention.

Ms Gavalas said Ingram had been taken from the holding cell to the chamber adjacent to the room where the electric chair is kept. He had made the same journey on Thursday before the original stay of execution.

She confirmed that he would be re-shaved to remove any remaining stubble which might hinder the electrocution - 24 hours after he was shaved in preparation for execution on Thursday.

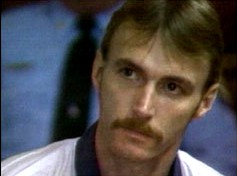

Nicholas Ingram goes to the chair

By Rupert Cornwell - The Independent (London)

April 9, 1995

THE FIRST four seconds were surely enough: 2,000 volts surging through Nicholas Ingram's body, before the charge was cut automatically, first to 1,000 volts and then to 208 volts. "Old Sparky" may be one of the unloveliest devices invented by man, but at 9.06pm here on Friday night it did its work exactly as intended.

As they positioned the metal cap on his head and fastened the brown leather mask over his face, Ingram's knuckles clenched tight on the arms of the electric chair. Then the executioner pressed the button. "He shot back in the chair with a tremendous jolt," said a witness. "There was no smoke, no sizzle, no sign of movement, nothing."

Thus ended the wretched odyssey of Nick Ingram, from broken home to drinking and petty crime, before his savage murder of JC Sawyer, a retired military veteran in an affluent Atlanta suburb in 1983. He spent the last 12 of his 31 years on Death Row, and he departed this life much as he had lived it - angry, defiant, and contemptuous of all around him.

At his own request he walked by himself to the electric chair. He said nothing, glaring one by one at the guards, prison officials and witnesses who watched him die, at even his own attorney. When the warden, Albert "Gerry" Thomas asked him if he had any last words, Ingram simply spat at him.

What remorse he had only emerged afterwards, through his lawyer, Mr Clive Stafford Smith. A specialist in death penalty cases, Mr Stafford Smith was distraught, choking back tears.

"Nicky wasn't very good at speaking. He asked me to make a statement for him. He asked me to say he wasn't the one getting hurt, but his family and the family of the Sawyers. He told me he hoped for something better now, because what had happened in this life had been so sad."

As the moment of death approached, a strange silence settled on those outside the prison, even among the small group of death penalty supporters who had cheered the hearse that would collect Ingram's body.Then Mrs Vicki Gavalas, the prison department spokeswoman, announced: "The order of the court has been carried out. Nicholas Lee Ingram was pronounced dead at 9.15 pm."

And others will follow him. More than 3,000 inmates are on Death Row in the US, 112 of them in H-5 block here at the Diagnostic and Classification Center - a euphemism of which Heinrich Himmler would have been proud for Georgia's maximum security prison.

Almost certainly, 1995 will set an annual record for executions in the US since capital punishment resumed 18 years ago, as labyrinthine appeal processes are exhausted and the country's thirst for vengeance against violent criminals grows.

In Georgia the only rights are victims' rights, the only complaint that Ingram didn't get his deserts far sooner.

"Justice delayed is justice denied," said Mike Bowers, the state's attorney general as he left the prison having watched Ingram die. "Our system should work better, 12 years is just too long." And if the chair is terrifying, that is as it should be. "You can't turn an execution into a surgical procedure."

In fact, albeit for very different reasons, advocates and opponents of capital punishment agree that the average 11 years an executed felon spends on Death Row makes a mockery of the process. Mr Bowers sees a legal system gone berserk, offering criminals the chance to escape punishment.

For the minority like Clive Stafford Smith, a process under which his client lives in the shadow of death for a decade is an obscenity.

"Well, he's dead now and they can't hurt him no more," said Johnny Ingram, Nick Ingram's father yesterday.

Ann and Johnny Ingram last saw their son eight hours before his execution, writes Steve Boggan. He had worn a baseball cap to spare them the traumatic sight of his shaved head.

"There's nothing to be said. It has happened and nothing's going to bring him back," said Ann Ingram. "Now we must pick up the pieces of our lives."

26 F.3d 1047

63 USLW 2096

Nicholas Lee INGRAM,

Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

Walter D. ZANT, Warden, Georgia

Diagnostic and

Classification Center, Respondent-Appellee.

No. 93-8473.

United States Court

of Appeals,

Eleventh Circuit.

July 12, 1994.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia.

Before HATCHETT, COX and BIRCH, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM:

Petitioner, Nicholas L. Ingram, filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus pursuant to 28 U.S.C. Sec. 2254, seeking collateral relief from his conviction and sentence of death. In his petition to the district court, Ingram raised twenty-seven different challenges to his conviction and sentence.

On September 10, 1992, the district court denied relief without conducting an evidentiary hearing. Ingram appealed, challenging the district court's conclusions with respect to six of his claims as well as the court's failure to conduct an evidentiary hearing on the merits of his contentions. Because we conclude that the district court correctly denied relief, we affirm.

I. BACKGROUND

On November 20, 1983, a jury sitting in Cobb County, Georgia, found petitioner, Nicholas Ingram, guilty for the June 3, 1983, malice murder of J.C. Sawyer.1 The facts of this crime are recounted in the Georgia Supreme Court's opinion in Ingram v. State, 253 Ga. 662, 323 S.E.2d 801, 805-06 (1984), cert. denied, 473 U.S. 911, 105 S.Ct. 3538, 87 L.Ed.2d 661 (1985).

During the sentencing phase, the jury found the existence of one statutory aggravating circumstance, i.e., that the murder was committed while Ingram was engaged in the commission of another capital felony (robbery). The jury sentenced Ingram to death. On appeal, the Georgia Supreme Court affirmed Ingram's convictions and sentences. Ingram, 253 Ga. 662, 323 S.E.2d 801.

On September 23, 1985, after exhausting his direct appeals, Ingram filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the Superior Court for Butts County, Georgia. The Superior Court conducted an evidentiary hearing on December 7, 1987, and denied Ingram's petition for habeas corpus on April 26, 1988.

The Georgia Supreme Court denied Ingram's motion for a certificate of probable cause to appeal on June 30, 1988, and he exhausted his state collateral appeals when the United States Supreme Court denied his petition for writ of certiorari on November 28, 1988. Ingram v. Kemp, 488 U.S. 975, 109 S.Ct. 514, 102 L.Ed.2d 549 (1988).

On January 4, 1989, Ingram filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, and the district court entered an order staying his execution. In his petition for habeas corpus, Ingram raised a myriad of issues challenging both his conviction and sentence. After the district court denied his petition for habeas corpus, Ingram filed a motion to alter and amend the judgment. The district court denied Ingram's motion. He appeals.

II. PARTIES' CONTENTIONS

Ingram contends that a majority of the jurors who voted for death believed that he would either be paroled within seven years if sentenced to life or never be executed if sentenced to death, making its sentence of death unreliable under the Eighth Amendment. He further contends that the jury imposed death only because it believed that he would serve more time in prison under a death sentence than under a life sentence. The government contends that the jury's sentence was reliable within the meaning of the Eighth Amendment and that further evidentiary development on this issue is unnecessary.

III. ISSUE

Although Ingram raises six issues on appeal, the only one we address is whether his death sentence is unreliable and a violation of his rights under the Eighth Amendment because of the jury's alleged erroneous beliefs regarding parole and the imposition of a death sentence.

IV. DISCUSSION

During the voir dire prior to Ingram's trial, the trial court permitted defense counsel to ask potential jurors whether they believed a person sentenced to death would actually be executed, and whether a person sentenced to life imprisonment would be paroled. Specifically, defense counsel asked the potential jurors if they believed that Ingram would actually be electrocuted if given the death penalty, and if given a life sentence whether he would eventually be released from prison.

Based on the individual juror's responses, defense counsel asked them additional questions regarding their beliefs. The following colloquies, recounting two jurors' responses, are representative of this line of questioning during the voir dire:

Juror Viney

[Defense counsel]: Okay. Do you think if the defendant in this case is given the death penalty that he will actually be electrocuted?

Juror: No, sir.

[Defense counsel]: Why do you say that?

Juror: Just past history.

[Defense counsel]: Okay. Do you think if he's given a life sentence that he would eventually be released from prison?

Juror: Yes, sir. Same reason.

Juror Deville

[Defense counsel]: Now, Mr. Deville, if the defendant is given the death penalty in this case, do you think that he will be electrocuted?

Juror: I seriously doubt it.

[Defense counsel]: Why do you say that?

Juror: Well, just the past history of the leniency of the judicial system, the parole system.

[Defense counsel]: Do you think if the defendant is given a life sentence that he would eventually be released from prison?

Juror: I think it's very possible.

[Defense counsel]: Why do you say that?

Juror: For the same reason, the track record and history of the judicial and parole system.2

The Georgia Supreme Court, in its opinion, describes this portion of the voir dire of potential jurors as follows:

Defendant asked potential jurors on voir dire whether they believed defendant would actually be executed if sentenced to death. The voir dire transcript shows that none of the jurors believed that an execution would be imminent and many expressed doubts that it would be carried out at all, in view of the infrequency of executions in recent years and the seemingly never-ending review of capital cases.

On the basis of these answers, defendant challenged the array at the close of voir dire, contending these jurors would be incapable of meaningful deliberation on the question of punishment and would be prone to impose the death penalty.

Ingram, 323 S.E.2d at 811.

Against this backdrop, defense counsel challenged the jurors who expressed such views and challenged the entire array, arguing that the jury "could be more prone to give the death penalty as a sentence more likely than not because of their belief that it will never be carried out...." The trial court rejected this argument, and refused to remove individual jurors or to strike the array.

Following his conviction, Ingram appealed challenging the validity of his death sentence and arguing "that he was entitled to a jury which believed the death penalty would be carried out." Ingram v. State, 323 S.E.2d at 811. Citing several Georgia cases rejecting similar claims, the Georgia Supreme Court rejected Ingram's contention: "defendant's argument that he is entitled to a jury which believes the death penalty would actually be carried out ... has previously been rejected." Ingram, 323 S.E.2d at 811.

In this appeal, Ingram contends that the jurors' misconceptions regarding the imposition of the death sentence render his sentence unreliable in violation of the Eighth Amendment. He argues that because the jurors did not believe he would actually be executed and that a life sentence would result in parole after seven years, they sentenced him to death solely to keep him in prison for the longest possible time.

Essentially, Ingram contends that a jury that believes the defendant will not be executed if sentenced to death is constitutionally unreliable within the meaning of the Eighth Amendment. Stated another way, Ingram asserts an Eighth Amendment right to a jury that believes that a death sentence will actually result in an execution. Because the Georgia Supreme Court held that Ingram maintains no state right to a jury that believes he would be executed if sentenced to death, we only consider whether such a right arises under the Federal Constitution.3 We conclude that it does not.

In support of his contentions, Ingram invokes Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472 U.S. 320, 328-29, 105 S.Ct. 2633, 2639-40, 86 L.Ed.2d 231 (1985), where the Supreme Court held it "constitutionally impermissible to rest a death sentence on a determination made by a sentencer who has been led to believe that the responsibility for determining the appropriateness of the defendant's death rests elsewhere."

In Caldwell, the prosecuting attorney urged the jury not to view itself as determining whether the defendant would be executed because the defendant was automatically entitled to appeal the decision to the Mississippi Supreme Court. Caldwell, 472 U.S. at 325, 105 S.Ct. at 2637.

Focusing on the risks inherent in arguments that inform a jury of the capital defendant's right to appellate review, the Court vacated the petitioner's sentence as unreliable under the Eighth Amendment. The Court reasoned that such arguments were likely to lead a jury to impose the death sentence out of a desire to avoid responsibility for its decision, and therefore, created the danger of the defendant being executed absent a determination that death was the appropriate punishment. Caldwell, 472 U.S. at 332, 105 S.Ct. at 2641.

Contrary to Ingram's suggestion, the issue he raises does not implicate the protections that the Supreme Court established in Caldwell.4 The error Ingram asserts here concerns misconceptions regarding the availability of parole which the jury allegedly maintained prior to being empaneled and instructed on the law, not improper prosecutorial arguments. Such alleged misconceptions do not fall under the rubric of Caldwell's proscription of improper closing arguments or similar errors.

At no point during his closing arguments did the prosecutor attempt to minimize the jury's role in deciding whether death was the appropriate sentence. Nor did the prosecutor argue to the jury that an appellate court would be reviewing its sentencing decision.

Although the prosecutor argued that Ingram's future dangerousness warranted the imposition of a death sentence, such argument does not minimize the jury's role, but rather impresses upon the jury the gravity of its decision. Tucker v. Kemp, 762 F.2d 1496, 1508 (11th Cir.) (en banc ), cert. denied, 478 U.S. 1022, 106 S.Ct. 3340, 92 L.Ed.2d 743 (1985). Such arguments are clearly permissible. Tucker, 762 F.2d at 1508.

Ingram further cites Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862, 103 S.Ct. 2733, 77 L.Ed.2d 235 (1983), to support his assertion that where the sentencer potentially based its decision in part on erroneous or inaccurate information, the death penalty must be reversed. In Zant, the Supreme Court stated, in footnote 23, that: "even in a noncapital sentencing proceeding, the sentence must be set aside if the trial court relied at least in part on 'misinformation of constitutional magnitude' such as prior uncounseled convictions that were unconstitutionally imposed." Zant, 462 U.S. at 887 n. 23, 103 S.Ct. at 2748 n. 23.

Aside from appearing as dicta regarding misconceptions of a trial judge, the Court's analysis in footnote 23 does not mention jury misconceptions regarding parole, and clearly specifies the sentencer's consideration of uncounseled convictions that were unconstitutionally imposed. Because the issue in Zant arose as a result of the petitioner's challenge to an erroneous jury instruction, the Court's reasoning does not apply to this case. Moreover, as we discuss below, the language in Zant is not persuasive because the error Ingram alleges in this case was not an error of "constitutional magnitude."

Finally, Ingram relies upon the Fifth Circuit's decision in Knox v. Collins, 928 F.2d 657 (5th Cir.1991), which, although factually similar, is analytically distinct. After allowing the defendant to inquire into the prospective juror's misconceptions regarding parole and whether the defendant would be executed if sentenced to death, the trial court in Knox led the defendant to believe that it would instruct the jury on the law regarding parole eligibility prior to sentencing. Knox, 928 F.2d at 658-60.

Based on such assurances, the defendant did not peremptorily exclude any jurors who expressed the view that the defendant would be paroled if sentenced to life in prison. Knox, 928 F.2d at 659. After the defendant failed to exercise his peremptory challenges, however, the trial court refused to give the requested parole instruction that would have corrected juror misconceptions about the actual meaning of a life sentence. Knox, 928 F.2d at 660.

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit granted habeas corpus relief upon concluding that the trial judge's statements during voir dire impaired "Knox's right to challenge certain members of the venire peremptorily[.]" Knox, 928 F.2d at 661.

Although the court recognized that defendants have no constitutional right to instruction on parole in capital cases, it reasoned that the trial judge's unkept promise to instruct the jury deprived Knox of a fair opportunity to exercise the peremptory challenges he was provided pursuant to Texas law. Knox, 928 F.2d at 661.

In this case, the trial court made no promises, implicit or otherwise, that it would instruct the jury regarding parole. Although the court permitted Ingram to inquire into the individual jurors' perceptions regarding parole and the significance of a death sentence, it did nothing to deprive him "of a fair exercise of the peremptory challenges he was accorded by [Georgia] law." Knox, 928 F.2d at 661. Because the trial court in no way impaired Ingram's use of peremptory strikes, and the court in Knox rested its opinion on that circumstance, Knox and its underlying holding is inapposite.

More on point is California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992, 103 S.Ct. 3446, 77 L.Ed.2d 1171 (1983), where the Supreme Court considered a constitutional challenge to a California statute that required trial courts, in capital cases, to instruct the jury about the governor's power to commute a sentence of life without possibility of parole. In rejecting petitioner's claim that the instruction misleads juries, the Court held that such a disclosure is constitutionally permissible but not constitutionally required. Ramos, 463 U.S. at 1002-09, 103 S.Ct. at 3454.

Then, upholding the trial court's failure to instruct the jury on the governor's power to commute a death sentence, the Court stated: "Our conclusion is not intended to override the contrary judgment of state legislatures that capital sentencing juries in their States should not be permitted to consider the Governor's power to commute a sentence.30" Ramos, 463 U.S. at 1013, 103 S.Ct. at 3460. In footnote 30, the Court further noted that, "[m]any state courts have held it improper for the jury to consider or to be informed--through argument or instruction--of the possibility of commutation, pardon, or parole." Ramos, 463 U.S. at 1013 n. 30, 103 S.Ct. at 3460 n. 30.

The Court's reasoning in Ramos demonstrates that although it is constitutionally permissible to instruct the jury regarding the possibility and effects of parole, the Federal Constitution does not require such an instruction. See also Knox, 928 F.2d at 60; Turner v. Bass, 753 F.2d 342, 353-54 (4th Cir.) (during sentencing phase of state capital murder prosecution, petitioner is not entitled, in response to jury's request during deliberations as to what life imprisonment entailed, to instruction on parole), cert. granted in part, 471 U.S. 1098, 105 S.Ct. 2319, 85 L.Ed.2d 838 (1985), and rev'd on other grounds sub nom. Turner v. Murray, 476 U.S. 28, 106 S.Ct. 1683, 90 L.Ed.2d 27 (1986).

Taking this reasoning one step further we have held that defendants maintain no cognizable federal right to prevent the jury, during the sentencing phase of a capital trial, from considering the possibility of parole if sentenced to life imprisonment. Dobbs v. Zant, 963 F.2d 1403, 1411 (11th Cir.1991), rev'd and remanded on other grounds, --- U.S. ----, 113 S.Ct. 835, 122 L.Ed.2d 103 (1993). See also United States v. Delgado, 914 F.2d 1062, 1066-67 (8th Cir.1990) (defendant not entitled to jury instruction that law would mandate five-year minimum sentence for conviction despite contention that jurors might presume that court had power to impose lighter sentence).

In Dobbs, petitioner challenged his death sentence contending that the jury improperly considered his eligibility for parole. During sentencing deliberations the jury foreman asked the trial judge about parole: "We the jury would like to know on the--say a felony from 1 to 10 years, we would sentence them to 10 years, would he be eligible for parole within 10 years?" Dobbs, 963 F.2d at 1411.

The trial court refused to answer the question, and the jury ultimately sentenced Dobbs to death. Dobbs appealed the district court's denial of his petition for habeas corpus arguing that the jurors' question demonstrated that the jury improperly considered his eligibility for parole.

In rejecting his claim, this court held that the trial court did not commit a constitutional error when it refused to answer the jurors' question, or otherwise clarify the issue of the defendant's parole eligibility. In doing so, we reasoned that a capital defendant has no federal right to prevent the sentencing jury from considering the possibility that he will be paroled if sentenced to life imprisonment. Dobbs, 963 F.2d at 1411.

Further, we concluded, because such a right was not cognizable under the Federal Constitution, the trial court's failure to instruct the jury to disregard the possibility of parole could not have violated the United States Constitution. Dobbs, 963 F.2d at 1411.

At the time of his sentencing, Ingram possessed neither a federal right to prevent a jury from considering parole nor a federal right to have a jury properly instructed on parole. Dobbs, 963 F.2d at 1411. Ramos, 463 U.S. at 1002-09, 103 S.Ct. at 3454-58.

Likewise, we are unable to find, in the precedents of the Supreme Court or this court, the existence of an Eighth Amendment right to be sentenced by a jury that believes that a death sentence will result in the defendant's execution. Although Ingram attempts to gather authority for this right from constitutional principles discussed in Caldwell, Zant and Knox, none of those cases support the novel argument he advances here.

We therefore hold that Ingram had no right to a jury that believed he would be executed if it sentenced him to death. While a state is free to provide such a right to a defendant, such a right is not constitutionally mandated in a capital case. See Ramos, 463 U.S. at 1002-09, 103 S.Ct. at 3454-58; O'Bryan v. Estelle, 714 F.2d 365, 389 (5th Cir.1983) (although states may require instructions on parole in capital trials, such instructions are not constitutionally mandated), cert. denied, 465 U.S. 1013, 104 S.Ct. 1015, 79 L.Ed.2d 245 (1984).

We are aware of the Supreme Court's mandate that because death qualitatively differs from any other permissible form of punishment, "there is a corresponding difference in the need for reliability in the determination that death is the appropriate punishment in a specific case." Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 305, 96 S.Ct. 2978, 2991, 49 L.Ed.2d 944 (1976) (footnote omitted).

We are further cognizant that a jury's determination of an appropriate sentence must be individualized based on the character and the particular circumstances of the crime. Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104, 110-12, 102 S.Ct. 869, 874-75, 71 L.Ed.2d 1 (1982).

In this case we find no intrinsic unreliability arising from the jury's alleged misconceptions regarding parole and the imposition of death. Nor do we find any basis for concluding that the jury did not reach an individualized decision on the appropriate sentence based upon the character and the circumstances of Ingram's crime.

Over the course of the entire trial, including voir dire, no juror expressed a position regarding Ingram's guilt or a predisposition to vote in favor of death. See Morgan v. Illinois, --- U.S. ----, ----, 112 S.Ct. 2222, 2232-33, 119 L.Ed.2d 492, 506-07 (1992); Ross v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 81, 85, 108 S.Ct. 2273, 2276-77, 101 L.Ed.2d 80 (1988).

Moreover, no juror stated or demonstrated that the allegedly flawed beliefs regarding parole or the imposition of death would infect their decisional process. Even so, any potential unreliability arising from those alleged misconceptions was cured when the trial court instructed the jury that it must follow the law: "[m]embers of the jury, you have found the defendant guilty of the offense of murder and it is now your responsibility to determine, within the limits prescribed by law, the penalty that shall be imposed for the offense." The court further instructed the jury that:

no recommendation that the defendant be put to death is proper under the law unless it is based solely on the evidence received by the jury in open court during both phases of these proceedings and unless the recommendation is not influenced by passion, prejudice or any other arbitrary factor.

(Emphasis added.) Because we presume that jurors follow such instructions, we must assume that the jury put aside any biases it may have had, applied the legal standards as enunciated in the jury instructions, and based its sentencing decision solely on the facts introduced at trial and sentencing. United States v. Brown, 983 F.2d 201, 202-03 (11th Cir.1993).

Finally, having elicited statements which he believed demonstrated impartiality or unreliability, Ingram was free to peremptorily exclude any of the prospective jurors from sitting in the case. He chose not to do so. As noted earlier, the trial judge did not impair Ingram's exercise of peremptory strikes in any way.

Because Ingram fails to show that he has an Eighth Amendment right to a jury that believes a death sentence will actually be enforced, and the circumstances of this case do not demonstrate that the jury's sentence of death was unreliable, we reject Ingram's claim and affirm the district court's denial of habeas corpus relief.5

In addition to his Eighth Amendment claim, Ingram also contends that: (1) the trial judge's improper remarks regarding a decade of appeals violated the Eighth Amendment; (2) the trial court's burden-shifting charges violated his constitutional rights; (3) the penalty phase instructions prohibited the jury from individually considering mitigating evidence; (4) the trial judge's law clerk's acceptance of employment with the district attorney's office during his capital prosecution denied him due process; and (5) the district court should have granted an evidentiary hearing on his claim that the prosecutor's failure to disclose a deal with the state's key witness denied him a fair trial. We have reviewed these claims and conclude that each lacks merit. Thus, we affirm the district court's denial of the writ of habeas corpus.

V. CONCLUSION

Capital defendants possess no right under federal law to a jury that imposes a death sentence believing that a sentence of death will result in the defendant's execution. Because no such right exists, Ingram's claim that he was entitled to a jury that believed he would be executed if sentenced to death is not cognizable under the United States Constitution.

AFFIRMED.

*****

Ingram was also indicted and convicted for the aggravated assault of J.C. Sawyer's wife, Mary Sawyer, and the armed robbery of Mary and J.C. Sawyer occurring on June 3, 1983. The trial court sentenced Ingram to twenty years imprisonment for the aggravated assault of Mrs. Sawyer and consecutive life sentences for the armed robbery of Mrs. Sawyer and the decedent

Both juror Viney and juror Deville sat on the jury that decided Ingram's case. Eleven of the final twelve jurors gave similar responses, indicating that they did not believe that Ingram would actually be executed if they voted in favor of the death penalty. Eight jurors emphatically stated that Ingram would not actually be executed even if sentenced to death. With respect to parole and the possibility of a life sentence, two jurors thought that parole would be available after seven years, and seven jurors believed that Ingram would be paroled on a life sentence at some time

The district court denied relief on this claim based upon rule 606(b) of the Federal Rules of Evidence which prohibits inquiry into the validity of a jury's verdict by using post-decision statements. Because we affirm the district court's decision based on other grounds, we do not consider the propriety of the district court's 606(b) analysis

Ingram does raise a pure Caldwell issue as one of his issues on appeal. This claim, however, arose from a comment the trial judge made to a juror who asked to use the phone during the jury's deliberations. In its comments to the juror, the court stated: "It's not a big thing, but it's just that the jury is not--In a death case, you see, in ten years, maybe somebody will say something about it." Because we conclude that Ingram's pure Caldwell claim lacks merit, we need not discuss it further here

Since oral argument in this case, the Supreme Court decided Simmons v. South Carolina, --- U.S. ----, 114 S.Ct. 2187, 129 L.Ed.2d 133 (1994) (plurality), where it held that a state trial court's refusal to instruct the jury, during the penalty phase of a capital trial, that under state law the defendant was ineligible for parole violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In Simmons the defendant requested a jury instruction which informed the jury that under state law he was ineligible for parole, after the prosecutor placed the defendant's future dangerousness at issue. Simmons, 62 U.S.L.W. at 4510, --- U.S. at ----, 114 S.Ct. at ----. The state trial court refused the request, and upon granting the writ of certiorari, a plurality of the Court held that where a defendant's "future dangerousness [is] at issue, he [is] entitled to inform the jury of his parole ineligibility." Simmons, 62 U.S.L.W. at 4514, --- U.S. at ----, 114 S.Ct. at ----

The Court's holding in Simmons does not affect our conclusion. Even assuming that the decision is retroactive, see Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288, 311-12, 109 S.Ct. 1060, 1075-76, 103 L.Ed.2d 334 (1989) (new rule will be applied retroactively only if it concerns bedrock procedural elements which enhance accuracy of trial court's decision), it does not help Ingram in this case because he never requested the trial court to instruct the jury regarding the significance of life imprisonment. See United States v. Hines, 955 F.2d 1449, 1453 (11th Cir.1992) (where defendant did not request instruction, trial court's failure to instruct the jury on the elements of a proffered defense did not constitute plain error). Moreover, the circumstances of Simmons are inapposite to the facts of this case because prior to May 1, 1993, Georgia law did not provide for life imprisonment without parole. See Ga.Code Ann. Sec. 17-10-16(b) (Michie Supp.1993). Thus, had Ingram received a life sentence for the murder of J.C. Sawyer, he could have been eligible for parole in a minimum of thirty years. See Ga.Code Ann. Sec. 42-9-39(c) (Michie 1991); and supra, note 1, at 2.

United States Court of Appeals,

Eleventh Circuit.

Nicholas Lee INGRAM, Plaintiff-Appellant,

Allen L. AULT, Jr., and in his capacity as Commissioner of Georgia Department of Corrections, Albert G. Thomas, Warden, as an individual and in his capacity as Warden of the Georgia Diagnostic & Classification Center at Jackson, Georgia, John Doe, as an individual and in his capacity as the Georgia State Executioner, Defendants-Appellees.

April 6, 1995.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia. (No. 95-CV-875-HTW), Horace T. Ward, Judge.

Before HATCHETT, COX and BIRCH, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM:

Appellant Nicholas Ingram is currently on death row in Georgia. Less than a week before his scheduled execution, Ingram filed a civil rights action in which he moved for a temporary restraining order enjoining his pending electrocution. The district court denied Ingram's motion. We affirm.

We previously denied Ingram's petition for a writ of habeas corpus in Ingram v. Zant, 26 F.3d 1047 (11th Cir.1994). On February 21, 1995, the United States Supreme Court denied Ingram's petition for a writ of certiorari. Ingram v. Thomas, --- U.S. ----, 115 S.Ct. 1137, 130 L.Ed.2d 1097 (1995). Ingram's execution was then scheduled for 7:00 p.m. on April 6, 1995.

On March 31, 1995, Ingram filed this lawsuit pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 against appellees, officials of the Georgia Department of Corrections, in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia.

Ingram alleges that: (1) execution by electrocution constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments; (2) appellees' policies will deny him face-to-face contact with his spiritual advisor during the hours immediately preceding his scheduled execution, and only provide a prison chaplain who is not of his faith as an alternative, in violation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments; and (3) appellees' policies will deny him face-to-face contact with his lawyer during the hours immediately preceding his scheduled execution in violation of the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments. On the same date, Ingram also filed a motion for a temporary restraining order (TRO), requesting the district court to enjoin "the unconstitutional use of the Electric Chair."

On April 4, 1995, the district court denied Ingram's motion for a TRO to enjoin his execution by electrocution. On April 5, 1995, the district court denied Ingram a TRO on his claims for face-to-face contact with his spiritual advisor and lawyer. [1]

Also on April 5, 1995, Ingram filed a motion to expedite his appeal and for oral argument. On the morning of April 6, 1995, we granted Ingram's motion for an expedited appeal and granted the parties an opportunity to provide additional briefing until noon of that day. Appellees submitted additional briefing; Ingram did not. We now deny the motion for oral argument.

ISSUE

The issue on appeal is whether the district court abused its discretion in denying Ingram's motion for a TRO.

Though we concur with appellees' contention that this court does not have jurisdiction to review the district court's denial of Ingram's motion for a TRO pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b), we find that this court does have jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1). Ordinarily, the denial of a motion for a TRO is not appealable under § 1292(a)(1). Cuban American Bar Ass'n, Inc. v. Christopher, 43 F.3d 1412, 1421 (11th Cir.1995). TRO rulings, however, are subject to appeal as interlocutory injunction orders if the appellant can disprove the general presumption that no irreparable harm exists. McDougald v. Jenson, 786 F.2d 1465, 1473 (11th Cir.), cert. denied, 479 U.S. 860 , 107 S.Ct. 207, 93 L.Ed.2d 137 (1986).

Furthermore, "when a grant or denial of a TRO "might have a "serious, perhaps irreparable, consequence," and ... can be "effectually challenged' only by immediate appeal,' we may exercise appellate jurisdiction." Romer v. Green Point Sav. Bank, 27 F.3d 12, 15 (2d Cir.1994) (quoting Carson v. American Brands, Inc., 450 U.S. 79, 84 , 101 S.Ct. 993, 997, 67 L.Ed.2d 59 (1981)). Because the district court denied Ingram's motion for a TRO, he faces execution in less than twenty-four hours. The requirements of irreparable harm and need for immediate appeal are therefore satisfied. Thus, we have jurisdiction over this action. [2] (1992), we decline to address that issue.

We review the district court's ruling for abuse of discretion. Majd-Pour v. Georgiana Community Hosp., 724 F.2d 901, 902 (11th Cir.1984). To be entitled to a TRO, a movant must show: (1) a substantial likelihood of ultimate success on the merits; (2) the TRO is necessary to prevent irreparable injury; (3) the threatened injury outweighs the harm the TRO would inflict on the non-movant; and (4) the TRO would serve the public interest. Gresham Park Community Org. v. Howell, 652 F.2d 1227, 1232 n. 7 (5th Cir.1981). [3]

Regarding Ingram's Eighth Amendment claim, the district court, focusing on the first of these factors, held that "in light of the overwhelming legal preceden[ts] in the lower federal courts, including the Eleventh [a]nd Fifth Circuit[s,] ... plaintiff has not established a substantial likelihood that he will prevail on the merits of his claim."

This holding clearly did not constitute an abuse of discretion. We agree that, in light of precedent, Ingram is not likely to prevail on the merits of this claim. See Johnson v. Kemp, 759 F.2d 1503, 1510 (11th Cir.1985) ("The contention that death by electrocution violates the Eighth Amendment is frivolous."); Sullivan v. Dugger, 721 F.2d 719, 720 (11th Cir.1983) (denying motion for a TRO alleging that "the carrying out of appellant's death sentence by means of electrocution is cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments"); Spinkellink v. Wainwright, 578 F.2d 582, 616 (5th Cir.1978) (rejecting petitioner's contention that electrocution constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments), cert. denied, 440 U.S. 976 , 99 S.Ct. 1548, 59 L.Ed.2d 796 (1979).

Similarly, in its April 5, 1995 order, the district court found that Ingram had not established a substantial likelihood of success on the merits of his First Amendment claims. Specifically, the district court held that "the mere fact that a prison chaplain is of one particular faith" does not constitute an Establishment Clause violation.

The district court also determined that Ingram failed to show "how face to face contact [with his spiritual advisor] is essential to the practice of his religion during the hours prior to his death.... [T]his is not sufficient to establish that defendants' regulations substantially burden plaintiff's exercise of religion." We hold that the district court did not abuse its discretion in denying Ingram a TRO on his First Amendment claims. See Johnson-Bey v. Lane, 863 F.2d 1308, 1312 (7th Cir.1988) ("Prisons are entitled to employ chaplains and need not employ chaplains of each and every faith to which prisoners might happen to subscribe...."); Bryant v. Gomez, 46 F.3d 948, 949 (9th Cir.1995) (rejecting prisoner's section 1983 free exercise claim under "substantial burden" test). [4] assertions.

In sum, we agree with the district court's conclusions that Ingram did not establish a likelihood of success on the merits of any of his claims. Consequently, we need not address the other factors relevant to the TRO inquiry.

The district court did not abuse its discretion in denying Ingram's motion for a TRO. Accordingly, we affirm. [5]

AFFIRMED.

*****

FOOTNOTES

After the district court entered its initial order on April 4, 1995, Ingram immediately filed a notice of appeal. We read his notice of appeal to also include the district court's order of April 5, 1995.

[2] Because appellees did not argue in the district court the doctrine articulated in Gomez v. United States Dist. Court for the N. Dist. of Cal., 503 U.S. 653 , 112 S.Ct. 1652, 118 L.Ed.2d 293

[3] In Bonner v. City of Prichard, 661 F.2d 1206 (11th Cir.1981) (en banc), this court adopted as binding precednet all decisions of the former Fifth Circuit rendered prior to October 1, 1981.

[4] Also in its April 5, 1995 order, the district court noted that appellees agreed to allow Ingram telephonic access to his lawyer during the three hours immediately preceding his scheduled execution. The district court found that Ingram's "attorney appeared to concede that telephonic communication would satisfy plaintiff's right guaranteed under the Sixth Amendment to assistance of retained counsel[,]" and that, in any event, telephonic access would satisfy the Sixth Amendment. We agree and note that Ingram has not challenged the district court's

[5] The mandate shall issue on April 6, 1995 at 5:00 p.m.