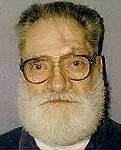

POTOSI, Mo. (AP) -- A man convicted of killing

two women was executed by injection early today after refusing for

years to appeal his case amid claims that a gunshot wound had

affected his judgment.

James H. Hampton, 62, did not seek clemency from

Gov. Mel Carnahan. As the first drug was administered, Hampton

raised his head, looked around and coughed a few times. His last

words: "Take the phone off the hook."

Hampton admitted beating Frances Keaton, 58, to

death with a hammer in 1992 after abducting her from her home in

Warrenton.

He then fled to New Jersey, where he killed

another woman, Christine Schurman, 48, during a kidnapping attempt.

As police moved in on Hampton, he stuck a gun

beneath his chin and shot himself. The bullet exited through the

front of Hampton's brain.

At his trial in 1996, a neurologist testified

that the brain wound affected Hampton's judgment. Death penalty

opponents blamed impaired judgment for Hampton's desire to die.

Hampton went to reform school at age 11 and spent his adult life in

and out of prisons.

Before his murder sentences, he served time in 25

different prisons for crimes ranging from burglary to assault to

drug trafficking.

Supreme

Court of Missouri

Case Number 79354

State of

Missouri, Respondent

v.

James Henry Hampton, Appellant

23/12/1997

Circuit Court of Callaway County, Hon. Frank Conley

Ronnie L. White, Judge

Opinion

James Henry Hampton appeals from his

conviction for the first degree murder of Frances Keaton and the

death sentence imposed for that crime.(FN1) We affirm.

Reviewing the evidence in the light

most favorable to the verdict,(FN2) the following facts were

established at trial.

At approximately 9:00 p.m. on the evening of

August 2, 1992, Mr. Hampton parked a green Pontiac Bonneville in the

lot of Fellowship Baptist Church in Warrenton. Mr. Hampton told

passersby that he was having car trouble, but declined offers of

assistance, saying that he had a bicycle. Leaving a note on his

windshield that read: "Car trouble. Gone for help. S.G. Gambosi,"

Mr. Hampton rode the bicycle about three miles to the neighborhood

where Frances Keaton lived.

Mr. Hampton knew, through his

acquaintance with Patricia Supinski--Ms. Keatonís realtor--that Ms.

Keaton and her fiancee, Allen Mulholland, had access to a checking

account containing at least $30,000. Using a copy of Ms. Keatonís

house key provided to him by Ms. Supinski, Mr. Hampton entered Ms.

Keatonís house dressed in dark clothing, wearing a stocking cap over

his face, and carrying a sawed-off shotgun.

Some time after 10

p.m., Mr. Hampton awoke Ms. Keaton and Mr. Mulholland, who were

asleep in their bedroom, and told them: "Iíve come here to rob you."

After binding Mr. Mulhollandís and Ms. Keatonís hands and feet, Mr.

Hampton demanded $30,000 from them. They replied that they didnít

have that much money, but Ms. Keaton said she thought that she could

get $10,000 from her pastor.

Mr. Hampton untied

her and allowed her to get dressed. When she attempted to escape,

Mr. Hampton overpowered her, and eventually placed a coathanger

around her neck and threatened to kill her if she again resisted him.

Mr. Hampton told Mr. Mulholland that he had a police scanner and

that, if the police learned of the kidnapping, he would kill Ms.

Keaton. Mr. Hampton then took Ms. Keaton outside to her car and

drove her towards the Supinski farm in Callaway County.

While they were

driving, at 1:15 a.m. on August 3, Mr. Hampton had Ms. Keaton call

her pastor on Mr. Mulhollandís cellular phone and ask him if he

could provide her with $10,000 cash by nine oíclock that morning.

The pastor was called her back on the cellular phone, but all

contact with Ms. Keaton was lost at 2:24 a.m.

At some point during the drive, Mr.

Hampton learned from his police scanner that law enforcement

authorities had been alerted to the kidnapping. According to his own

testimony, Mr. Hampton had decided in advance to kill his hostage if

police learned of the kidnapping before he received the ransom.

Carrying through with his plan, Mr. Hampton bound and blindfolded

Ms. Keaton and took her to a wooded area one half mile from the

Supinski farm. Once there, he killed Ms. Keaton with several hammer

blows to her head and then buried her body.

The morning after killing Ms. Keaton,

Mr. Hampton drove her car back to Warrenton, and attempted to

retrieve the green Pontiac he had left at the Fellowship Baptist

Church. He abandoned his attempt when he saw that police were

keeping the car under surveillance. Late that night, after police

had impounded the car, he was apprehended attempting to enter the

locked impound lot, but gave an alias and was released. After that,

Mr. Hampton fled the State and was eventually apprehended in New

Jersey, where he had committed another murder. As he was about to be

taken into custody, Mr. Hampton shot himself in the head.

Right to Self-Representation

Mr. Hampton contends that he was

denied his right to represent himself at trial. The Sixth

Amendmentís guarantee of assistance of counsel implies a correlative

right to dispense with such assistance.(FN3) A criminal defendant

who makes a timely, informed, voluntary and unequivocal waiver of

the right to counsel may not be tried with counsel forced upon him

by the State.(FN4) The determinative question, then, is whether Mr.

Hampton made such a waiver.

On September 18, 1995, ten months

before trial started, Mr. Hampton filed a "Motion/Demand/Notice for

Self-Representation" wherein he asked the court to enter an order "permitting

self-representation . . . as explained . . . in Faretta . . .

." At that time, he also filed an "Entry of Appearance," advising "all

persons connected [with the case] that he is now the attorney of

record . . ."

After hearing Mr.

Hampton argue his motion, the trial court suggested that it delay

ruling on the motion, but when pressed by Mr. Hampton, overruled it.

On October 13, Mr. Hampton again sought to have the motion for self-representation

taken up, but the court ruled that it would follow its original

ruling on the issue.

At that point, Mr.

Hampton filed a second entry of appearance and motion for self-representation,

and then sought a writ of prohibition in the court of appeals,

seeking to prohibit further proceedings until he was allowed to

represent himself. When that petition was denied, Mr. Hampton sought

similar relief in this Court, which was also denied in March of

1996. The trial court again heard argument from Mr. Hampton on July

5, and, on July 16, noted that it was continuing to rule against Mr.

Hamptonís request.

The relevant considerations in

evaluating a motion for self-representation were concisely set forth

by the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals in the recent case

Hamilton v. Groose:

A criminal

defendantís motion to represent himself involves two mutually

exclusive constitutional rights: the right to be represented by

an attorney, and the right not to be represented by an

attorney. A court must Ďindulge in every reasonable presumption

against [a defendantís] waiverí of his right to counsel,

Brewer v. Williams, 430 U.S. 387, 404, 97 S.Ct. 1232, 1242,

51 L.Ed.2d 424 (1977), and require the defendant to make a

knowing, voluntary, and unequivocal request before concluding

that he has waived his right to counsel and invoked his right to

represent himself.(FN5)

Recognizing that a

defendant who is allowed to proceed pro se may argue on

appeal that the right to counsel was improperly denied, the court

emphasizes that ambiguous requests for self-representation are not

sufficient: "The probability that a defendant will appeal either

decision of the trial judge underscores the importance of requiring

a defendant who wishes to waive his right to counsel to do so

explicitly and unequivocally."(FN6) What Faretta guarantees

is the right to forgo the assistance of counsel in defending oneself,

not the right to insist on self-representation in addition to

representation by counsel: "Faretta does not require a trial

judge to permit Ďhybridí representation . . . ."(FN7) "Because there

is no constitutional right for a defendant to act as co-counsel, the

refusal [to grant a defendantís motion for self-representation] does

not violate the dictates of Farretta."(FN8)

In his numerous filings and arguments

on this issue, Mr. Hampton never suggested that by asking to act as

his own lawyer, he intended to waive his right to be represented by

counsel. Mr. Hampton indicated, in arguing his motion to the trial

court, that it was intended to prevent his attorneys from making "certain

strategic decisions" in his case that he disagreed with. He argued

that attorneys "are to advise and represent, not to replace or

second-guess the defendant . . . . [I]f I am the attorney of record,

then I will be able to make that decision. I donít intend to conduct

the voir dire."

Mr. Hampton also

reported that he did not intend to conduct the cross-examination of

"many, if any of the witnesses." The tenor of Mr. Hamptonís argument

is accurately reflected by the trial courtís characterization: "At

this point in time youíre telling me that you want [defense counsel]

to represent you, you want them to do the voir dire, you want them

to cross-examine witnesses. But you want to have the final say-so."

In arguing that his conduct amounted

to unequivocal waiver of the right to counsel, Mr. Hampton relies

exclusively on United States v. Arlt, where the Ninth Circuit

Court of Appeals reversed a conviction because the defendantís right

to represent himself was violated.(FN9) That case is factually

distinguishable from the present matter. In Arlt, the

defendant expressed the desire to represent himself before counsel

had been appointed, and persisted in that position even when the

trial court sought to dissuade him from it by explaining the

disadvantages of forgoing the assistance of counsel.(FN10) Here, Mr.

Hampton never expressed the desire to completely forgo the

assistance of counsel and, without being prompted by the court,

expressed the desire that his lawyers conduct crucial aspects of the

case.

The

factual situation here is much more similar to another Ninth Circuit

case: United States v. Kienenberger.(FN11) In that

case, the defendant made numerous requests to be appointed "counsel

of record," but also requested that the court appoint advisory

counsel to assist him on procedural matters.(FN12) The court

affirmed the conviction, holding that defendant "never relinquished

his right to be represented by counsel at trial. His requests to

represent himself were not unequivocal."(FN13) As the Arlt

court held: "A defendant must make an explicit choice between

exercising the right to counsel and the right to self-representation

. . . ."(FN14)

In this case, Mr.

Hampton sought to have the best of both worlds. While the trial

court attempted to indulge Mr. Hamptonís requests to be heard along

with his attorney, it did not err in refusing to make him "attorney

of record," since that request did not amount to an unequivocal

waiver of the right to counselís assistance.

Waiver of Right

to Remain Silent

Mr. Hampton argues that his Fifth

Amendment right against self-incrimination was violated because the

trial court did not make a finding on the record that he had waived

the right "knowingly, voluntarily and intelligently" before he took

the stand and confessed to murdering Ms. Keaton. In support of this

contention, Mr. Hampton cites two cases, Boykin v. Alabama,(FN15)

and Rolfes v. State,(FN16) which hold that a trial court must

advise a defendant on the record of his right to remain silent

before accepting his guilty plea.

These cases are

plainly inapplicable here since before allowing Mr. Hampton to take

the stand the court advised him of his right not to testify, that

the court would instruct the jury that it could not infer guilt from

his failure to testify, that by testifying he was subjecting himself

to cross-examination, and that by testifying he was enabling the

prosecution to present evidence of his prior criminal record. Mr.

Hampton testified that he understood each of these admonishments,

but was nevertheless taking the stand against his attorneysí advice.

While Mr. Hampton now points to some

remarks made to the court-appointed psychiatrist who examined him

for competency that, viewed in a very stilted manner, arguably

suggest Mr. Hampton thought he had to put on evidence in order to

prove his innocence, he does not actually allege that the waiver was

not made knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily. Instead, he

asserts that the failure of the trial court to make that specific

finding on the record was erroneous. Because this claim was not made

to the trial court, giving it the opportunity to make the finding,

we review it for plain error only.(FN17)

Certainly no

miscarriage of justice occurred because the trial court did not

write the words "knowingly, voluntarily, and intelligently" in the

docket sheet. And even if we read Mr. Hamptonís argument much more

broadly than he has actually made it, the record completely

contradicts the idea that Mr. Hampton was not making an informed

decision in waiving his right to remain silent. Mr. Hampton

specifically and emphatically affirmed that he was aware of the

rights he was waiving. Justice is not offended by a man taking the

witness stand and accepting responsibility for the terrible acts

that he has committed.

Competency to

Stand Trial

As a result of Mr. Hamptonís self-inflicted

gunshot wound, he suffered damage to both the right and left frontal

lobes of his brain. Accordingly, he argues that he was not competent

to stand trial. "No person who as a result of a mental disease or

defect lacks capacity to understand the proceedings against him or

to assist in his own defense shall be tried, convicted or sentenced

for the commission of an offense so long as the incapacity

endures."(FN18) Upon defense counselís motion, two experts examined

Mr. Hampton.

The defenseís expert neurologist, Dr. Pincus, testified that, as

result of his examination, he concluded that Mr. Hamptonís frontal

lobe injury severely impaired his judgment, causing him paranoia

that impaired his ability to assist in his defense. He based this

conclusion on physical tests and on his interview with Mr. Hampton

where he exhibited that he did not trust his defense counsel or Dr.

Pincus.

Dr. Parwatikar, a

State forensic psychiatrist, examined Mr. Hampton, filed a report

and testified before the court. Dr. Parwatikar concurred that Mr.

Hampton had suffered some brain damage and was distrustful of his

defense counsel. He concluded, however, that Mr. Hampton did not

suffer from any mental disease or defect, and that he was able to

assist his attorney in his defense. The trial court explicitly found

Dr. Parwatikarís testimony to be more believable than that of Dr.

Pincus, and based upon that testimony and observation of the

defendantís behavior in court, found that Mr. Hampton was competent.

We defer to the factual findings of the trial court.(FN19)

Mr. Hampton contends that his case is

"almost directly on point" with the only case he cites in support of

his position: State ex rel. Sisco v. Buford.(FN20) In that

case, this Court prohibited the defendant from being tried because

he was unable to assist in his defense due to a self-inflicted

gunshot wound that damaged his frontal lobes.(FN21) The parallels

end there, however.

In that case, after

hearing expert testimony, the trial court entered its findings of

fact that: "defendant has no memory of the events of the date of the

alleged crime and cannot aid in his defense and that said loss of

memory is permanent and that defendant can never aid in his defense."(FN22)

Surely, Sisco

does not stand for the proposition that any person with a frontal

lobe injury is presumptively incompetent to stand trial. The factual

situation here is distinct. An expert report found, and the trial

court ruled, that Mr. Hampton suffered no inability to assist in his

defense. We will not reweigh the evidence and second-guess this

factual conclusion supported, as it is, by the expert testimony

presented to the trial court and the courtís own observation of the

defendantís behavior.

Mr. Hampton also concludes that Dr.

Parwatikar evaluated Mr. Hampton by the wrong standard in

determining whether he was competent. The proper standard, Mr.

Hampton asserts, is whether a defendant "has a sufficient present

ability to consult with his attorneys with a reasonable degree of

rational understanding and whether he has a rational as well as

factual understanding of the proceedings against him."(FN23) Mr.

Hampton does not attempt to explain, nor are we able to discern, how

this standard is, in any meaningful sense, not met by Dr.

Parwatikarís findings that Mr. Hampton "understands the charges

pending against him and has the capacity to assist his attorney in

his defense." The trial court did not err in ruling that Mr. Hampton

was competent to stand trial.

Seizure and

Search of Pontiac Bonneville

Mr. Hampton asserts that the trial

court erred in refusing to suppress items seized during the

warrantless search of the car he had left parked at Fellowship

Baptist Church while he committed the murder. Soon after Ms.

Keatonís kidnapping was reported, FBI agents investigating the crime

came to suspect that the Pontiac Bonneville parked at the church was

used in the crime. Accordingly, they had the car watched and

eventually, towed. Two days later, they searched the car and found

several items that were introduced against Mr. Hampton at trial.

These included a notebook and various documents in Mr. Hamptonís

handwriting, some indicating that he used the name S.G. Gambosi, a

file, a shotgun, and a map of Missouri.

Searches of automobiles, because they

are mobile, are generally excepted from the warrant requirement.(FN24)

While Mr. Hampton concedes that police may seize a vehicle and

search it later as long as they have probable cause at the time of

the seizure,(FN25) he contends that, in this case, no probable cause

to search the car existed at the time it was seized. While the State

bears both the burden of production and the burden of persuasion in

showing that a warrantless search is invalid,(FN26) we review the

facts in the light most favorable to the trial courtís ruling.(FN27)

The ultimate question of whether these facts are sufficient to

support probable cause is decided de novo.(FN28)

The evidence before the suppression

court consisted of the testimony of the two FBI agents who

investigated Ms. Keatonís kidnapping. The officers testified that

their attention was first drawn to the green Pontiac by the report

of a neighbor of Ms. Keatonís, Norma Smith, that she had seen a man

wearing dark clothes entering the neighborhood on foot at about ten

oíclock that night, and that she had this man earlier at her church.

She testified that she was startled to see him and that he had

seemed startled to see her.

In talking to other

parishioners, the FBI agents learned that the owner of the Pontiac

had been behaving unusually and had refused offers of a ride,

instead leaving on a bicycle. The agents concluded that a man on a

bicycle could easily ride from the church to the spot where Ms.

Smith saw the man in the approximately one hour between the

sightings.

The agents knew

that the kidnapper and Ms. Keaton had left in her car, and suspected

that the Pontiac might be have been used by the kidnapper to

approach the scene, since they had accounted for all other cars

parked in the vicinity. The agents checked the registration, which

showed that the car was registered to a Sam Gambosi. Although agents

found that the car had only been sold to "Gambosi" a week earlier,

the address he had given for the registration did not belong to any

one by that name, nor had anyone at that address ever heard of such

a person.

As

the United States Supreme Court has recently reiterated, probable

cause is a flexible, common-sense concept:

Articulating

precisely what . . . "probable cause" mean[s] is not possible. [It

is a] commonsense non-technical conception[] that deal[s] with

"Ďthe factual and practical considerations of everyday life on

which reasonable and prudent men, not legal technicians, act.í"

. . . . [P]robable cause to search . . . exist[s] where the

known facts and circumstances are sufficient to warrant a man of

reasonable prudence in the belief that contraband or evidence of

a crime will be found.(FN29)

Examining the facts

before the trial court, we find that probable cause to search was

present at the time the car was seized. The fact that its driver was

seen in the neighborhood where the crime was committed shortly

before it occurred, generally matched the description of the

kidnapper, had behaved somewhat suspiciously at the time the car was

parked, and the fact that the car was registered to a fictitious

address reasonably gave officers cause to believe that the Pontiac

was involved in Ms. Keatonís kidnapping, and that evidence of her

whereabouts or of the identity of her kidnapper could be found

therein. The trial court did not err in overruling the motion to

suppress the evidence seized from the Pontiac.

Separate Penalty

Phase Jury

Mr. Hampton claims that the trial

court erred in overruling his motion for a separate penalty phase

jury. As this Court has repeatedly held, this claim is meritless.(FN30)

Non-MAI

Cautionary Instruction

Mr. Hampton alleges that the trial

court erred in refusing to give a non-MAI cautionary instruction

prior to death penalty voir dire. The proffered instruction

indicated that the death qualification questions were routine and

did not imply guilt. This Court has consistently held, and we now

reiterate, that the refusal to give such an instruction is not

error.(FN31)

Reasonable Doubt

Instruction

Mr. Hampton contends that the

reasonable doubt instruction in MAI-CR3d 313.30, given in the

penalty phase of this case, deprived him of due process.

Specifically, Mr. Hampton challenges the language explaining that "[p]roof

beyond a reasonable doubt is proof that leaves you firmly convinced

of the truth of a proposition. The law does not require proof that

overcomes every possible doubt." As this Court has repeatedly found,

this language is consistent with the due process guarantee.(FN32)

Voir Dire

Defining Degrees of Murder

Mr. Hampton alleges error based on the

following exchange during voir dire:

[Defense

counsel]: Itís necessary for this next question that Iím going

to ask you that I give you a short kind of description of what

the law is as it relates to homicide. Now, youíve heard that Mr.

Hampton has been charged with murder in the first degree. That

is the highest level of homicide. Murder in the first degree we

define it as what we call deliberate murder. It is not the only

level of homicide. We also have something we call murder in the

second degree which is the next step down. And then we have two

forms of what we call manslaughter. So theyíre all four levels

of homicide. Murder in the first degree being the highest and

murder in the second degree being the next step down.

Now, as I said, murder in the

first degree is defined as deliberate murder. I think we used to

use the word "premeditated." But we donít use that any more. It

is called deliberate murder. It is defined by the law as cool

reflection for a period of time no matter how brief. Okay,

thatís our highest level. Deliberate murder.

Murder second degree is what we

call knowingly murdering someone. The difference between the two

goes to what we call the state of mind of the defendant.

[Prosecutor]: Judge, may we

approach the bench?

[At sidebar]:

[Prosecutor]: Iím going to object

to some what I perceive is a misstatement of the law. Trying to

distinguish second from first.

THE COURT: The objection will be

sustained. Letís proceed.

[Defense counsel]: Judge, may I

address the court on this?

I intend to ask the jury whether

in this or any other case theyíve learned that kidnapping is

involved or weapons involved they will automatically feel that

is murder in the first degree. I believe itís necessary to

define the difference between murder in the first degree and

murder in the second degree in order to place that question in

context. I believe Iím correctly defining those two levels of

homicide.

THE COURT: Well, I think I will

allow you to, if they consider one thing is automatic, but you,

I donít want you getting into the definitions of first and

second degree murder. You can ask them if they think that

kidnapping or something else would influence them in the case if

you want to. I donít think you really do want to, but if you

want to ask that question you can.

[Defense Counsel]: I do want to

ask that question.

. . . .

THE COURT: The objection will be

sustained as to the question that was put to the jury just now.

[Defense Counsel]: So the court is

allowing, just for clarification purposes, the court is allowing

me to ask about abduction and a weapon involved, but the court

is not allowing me to ask whether the juror would automatically

feel if a weapon or abduction or kidnapping is involved whether

that would be murder in the first degree?

THE COURT: Oh, if you want to ask

them if that automatically is murder in the first degree, you

are entitled to ask that.

[Defense Counsel]: I think itís

necessary to define the concept.

THE COURT: I donít want you to go

into the definitions of what is murder first and murder second.

[Defense Counsel]: I donít know

how to ask them if itís murder in the first degree without

telling them before I do that. I guess Iíve already done it. But

I mean I donít know.

THE COURT: The objection will be

sustained as asked. Letís proceed.

[In open court]:

[Defense counsel]: . . . . Does

anybody on this side of the room feel that if they heard that a

gun was involved in a case or an abduction, that they would

automatically conclude that this is murder in the first degree?

The nature and

scope of questions asked at voir dire is reviewed for abuse of

discretion.(FN33) Mr. Hampton argues that defense counsel was

prohibited from conducting voir dire on the issue of the difference

between the mental states required to find a defendant guilty of

first and second degree murder. Mr. Hampton cites State v. Brown,(FN34)

where this Court found reversible error in the trial courtís refusal

to allow the defense to ask potential jurors whether they would be

able to follow the law and require the State to meet its burden of

proving beyond a reasonable doubt that self-defense was not present.

Whether the

principle of Brown also applies to questions about degrees of

murder, however, need not be addressed, since the trial court here

did not actually prevent the defense from presenting information to

the jury or asking the question it sought to ask. As Mr. Hampton

notes in his brief, no question was actually before the panel at the

time objection was made, and no objection to a particular question

was sustained. Although defense counsel was told not to define

degrees of murder, he had, as he notes in the above colloquy,

already done so. The panel was not told to disregard this

information, and objection was not made to it within their hearing.

Defense counsel

asked his question about whether anyone would presume first degree

murder from the use of a gun, and several jurors responded that they

would. Under these circumstances there was no conceivable abuse of

discretion, since the trial court did not actually restrict the

ability of the defense to conduct the voir dire in the manner it

requested.

Voir Dire on Signing Death Verdict

Mr. Hampton argues that the trial

court erred in permitting the prosecution to ask potential jurors

whether they could sign a death verdict if chosen as foreperson.

This claim is baseless, and this Court has repeatedly rejected it.(FN35)

Failure to

Provide Child Care for Jurors

Mr. Hampton asserts that the trial

court erred in refusing to provide child care for jurors, because

that failure effectively, and unconstitutionally, excluded women and

poor people from the jury. This Court has already examined this

question and found that provision of child care for jury members is

not constitutionally mandated.(FN36)

We continue to follow that holding

here.

Admissibility of

Post-Mortem Photographs of the Victim

Mr. Hampton argues that nine

photographs of Ms. Keatonís corpse admitted into evidence were

unduly prejudicial. Three photographs were pictures of the body at

the site where it was buried by Mr. Hampton, as it was being

uncovered. Three were of the body as it was being readied for

transport, and three were photographs taken during the autopsy. Mr.

Hampton concedes that the trial court has broad discretion over the

admission of photos and its ruling will be affirmed absent an abuse

of that discretion.(FN37) Mr. Hampton also concedes that even

gruesome photos are admissible if they "corroborate the testimony of

a witness, . . . assist a jury better to understand the facts and

testimony of witnesses, [or] prove an element of the case."(FN38)

As Mr. Hampton

admits, the grave scene photographs were used by the State to

corroborate and illustrate the testimony of an officer and an

investigator who assisted in the excavation of the burial site. The

photographs reflected both the condition of the scene and the

condition of the body at the time of the excavation. As to the

autopsy photographs, they were relevant to corroborate and

illustrate the testimony as to the cause of Ms. Keatonís death. The

admission of these photographs was not an abuse of discretion.

Review of

Sentence

Mr. Hampton contends that his death sentence is unconstitutional

because this Court does not engage in "meaningful" proportionality

review. We have repeatedly rejected this argument,(FN39)

and continue to do so.

As required by section 565.035.3 we

review the record to ensure that the death penalty was properly

imposed in this case. There is no evidence in the record that the

sentence of death was imposed under the influence of passion,

prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor. Three aggravating

circumstances were found by the jury: that Mr. Hampton had a prior

serious assaultive criminal conviction;(FN40) that Mr. Hampton

committed the murder for the purpose of receiving money from the

victim or another;(FN41) and that the victim was killed in the

course of a kidnapping.(FN42) The evidence supports the finding of

one aggravating circumstance as required by 565.030.4(1), and

supports the other aggravating circumstances found.

Considering the crime, the strength of

the evidence, and the defendant, the sentence of death is

proportionate to similar cases. In this case, Mr. Hamptonís own

testimony establishes that he broke into Ms. Keatonís bedroom,

terrorized, kidnapped, bound and blindfolded her, took her to a

secluded area and killed her with complete detachment, in an utterly

brutal manner, when his plan to ransom her failed. The penalty

imposed in this case is not disproportionate to similar cases

involving executions in the course of kidnappings, cases where the

victim was brutally killed while bound and helpless, and killings

for money.(FN43)

Conclusion

The judgment of the trial court is

affirmed.

*****

Footnotes:

FN1. More accurately, Mr. Hamptonís appointed

counsel appeals; Mr. Hampton has filed a motion asking that his

conviction be summarily affirmed and an early execution date set.

FN2. State v. Shurn, 866 S.W.2d 447, 455 (Mo. banc 1993)

FN3. Faretta v. California, 95 S.Ct. 2525, 2539-40 (1975).

FN4. Id. at 2541.

FN5. 28 F.3d 859, 862 (8th Cir. 1994) (emphasis in original).

FN6. Id. at 863.

FN7. McKaskle v. Wiggins, 465 U.S. 168, 183 (1984).

FN8. Cross v. United States, 893 F.2d 1287, 1292 (11th Cir.

1990).

FN9. 41 F.3d 516 (9th Cir. 1994).

FN10. Id. at 517, 519-20.

FN11. 13 F.3d 1354 (9th Cir. 1994).

FN12. Id. at 1356.

FN13. Id.

FN14. Arlt, 41 F.3d at 519.

FN15. 395 U.S. 238 (1969).

FN16. 574 S.W.2d 948 (Mo. App. 1978).

FN17. Rule 30.20.

FN18. Section 552.020.1, RSMo 1994.

FN19. State v. Wilkins, 736 S.W.2d 409, 415 (Mo. banc 1987);

State ex rel. Sisco v. Buford, 559 S.W.2d 747, 748 (Mo. banc

1978); State v. Petty, 856 S.W.2d 351, 353 (Mo. App. 1993).

FN20. 559 S.W.2d at 747.

FN21. Id.

FN22. Id.

FN23. Dusky v. United States, 362 U.S. 402, 402 (1960).

FN24. State v. Lane, 937 S.W.2d 721, 722 (Mo. banc 1997).

FN25. Id. at 722-23; Chambers v. Maroney, 399 U.S. 42,

52 (1970).

FN26. Section 542.296.6, RSMo 1994.

FN27. State v. Rodriguez, 877 S.W.2d 106, 110 (Mo. banc

1994).

FN28. Ornelas v. United States, ___ U.S. ___, 116 S.Ct 1657,

1659 (1996)

FN29. Id. at 1661.

FN30. See, e.g., State v. Weaver, 912 S.W.2d 499, 522 (Mo.

banc 1995); State v. Parker, 886 S.W.2d 908, 921 (Mo. banc

1994); State v. Whitfield, 837 S.W.2d 503, 509-10 (Mo. banc

1992); State v. Kilgore, 771 S.W.2d 57, 63 (Mo. banc 1990).

FN31. See, e.g., Weaver, 912 S.W.2d at 522; Parker,

886 S.W.2d at 921; Kilgore, 771 S.W.2d at 63.

FN32. See, e.g., State v. Smulls, 935 S.W.2d 9, 22 (Mo. banc

1996); State v. Brown, 902 S.W.2d 287, 287 (Mo. banc 1995);

State v. Chambers, 891 S.W.2d 93,105 (Mo. banc 1994).

FN33. State v. Coats, 835 S.W.2d 430, 433 (Mo. App. 1992).

FN34. 547 S.W.2d 797 (Mo. banc 1977).

FN35. See e.g., State v. Chambers, 891 S.W.2d 93, 102

(Mo. banc 1994); Clemmons v. State, 785 S.W.2d 524, 529 (Mo.

banc 1990); State v. McMillin, 783 S.W.2d 82, 91-92 (Mo. banc

1990).

FN36. State v. Whitfield, 837 S.W.2d 503, 510 (Mo. banc

1992).

FN37. State v. McMillin, 783 S.W.2d 82, 101 (Mo. banc 1990).

FN38. Id.

FN39. See, e.g., State v. Weaver, 912 S.W.2d 499, 522 (Mo.

banc 1995); State v. Brown, 902 S.W.2d 278, 291 (Mo. banc

1995); State v. Whitfield, 837 S.W.2d 503, 515 (Mo. banc

1992).

FN40. Section 565.032.2(1), RSMo 1994.

FN41. Section 565.032.2(4), RSMo 1994.

FN42. Section 565.032.2(11), RSMo 1994.

FN43. State v. Simmons, No. 77439 (Mo. banc November 25,

1997); State v. Skillicorn, 944 S.W.2d 877 (Mo. banc 1997);

State v. Smith, 944 S.W.2d 901 (Mo. banc 1997); State v.

Basile, 942 S.W.2d 342 (Mo. banc 1997); State v. Copeland,

928 S.W.2d 828 (Mo. banc 1996); State v. Kreutzer, 928 S.W.2d

854 (Mo. banc 1996); State v. Tokar, 918 S.W.2d 753 (Mo. banc

1996); State v. Brown, 902 S.W.2d 278 (Mo. banc 1995);

State v. Six, 805 S.W.2d 159 (Mo. banc 1991).