Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia, at Richmond.

Robert E. Payne, District

Judge.

Before WILKINSON, Chief Judge,

and LUTTIG and MOTZ, Circuit Judges.

OPINION

PER CURIAM

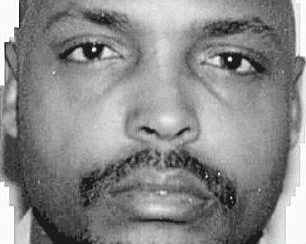

Carl Hamilton Chichester

appeals the district court's dismissal of his

petition for writ of habeas corpus, challenging

his conviction in Virginia state court for

capital murder. We deny Chichester's motion for

a certificate of appealability and dismiss the

appeal. 1

I.

At approximately 10:30 p.m.

on August 16, 1991, two black men entered a

Little Caesars pizza restaurant in Manassas,

Virginia, wearing dark clothing, masks, and

gloves, and carrying semi-automatic pistols.

One

man was about three inches taller than the other.

The shorter man jumped over the counter, took

money from one of the two cash registers, and

demanded that Timothy Rigney, the manager of the

restaurant, open the second register.

The taller

man remained on the customer side of the counter.

Rigney attempted to open the register, but was

unable to do so. When Rigney indicated that he

could not open

the register, one of the two men shot and killed

him. The two men then fled the scene on foot.

Because both men were masked,

none of the four eyewitnesses to the murder

could identify either of them. However, Jack

Burdette, a man who was in the vicinity at the

time of the murder, told police that night that

he had seen two men wearing dark clothing

running from the direction of the restaurant.

On February 18, 1993,

Burdette told police that he had recognized one

of the two men as appellant Carl Hamilton

Chichester ("Chichester"). He later testified

that he had not named Chichester on the night of

the murder because he was concerned about the

safety of his family.

Of the three eyewitnesses who

testified at trial, two testified that they

thought that the man on the customer side of the

counter -- believed to be Chichester -- was the

shooter, and one testified that she was unsure

which man was the shooter. Denise Matney, an

employee, originally told police that she was

unsure which man was the shooter, but testified

at trial that it was the man on the customer

side of the counter.

Robert Harris, a customer,

also testified that the man on the customer side

of the counter was the shooter. Patricia Eckert,

Harris' girlfriend, originally told police that

she thought that the man on the employee side of

the counter was the shooter, but testified at

trial that she was unsure of the identity of the

shooter b ecause she had buried her face in

Harris's chest in fright. A fourth eyewitness,

William Fruit, a 16-year-old employee, was

unavailable to testify at trial, but originally

told police that he thought that the man on the

employee side of the counter was the shooter.

At trial, the prosecution

introduced evidence relating to an earlier

robbery of Joe's Pi zza for which Chichester and

his alleged accomplice had been convicted.

On

August 7, 1991, nine days before the Little

Caesars robbery, two black men entered Joe's Pizza in Manassas, wearing dark clothing, masks,

and gloves, and carrying semiautomatic pistols.

One man was noticeably taller than the other.

The shorter man proceeded immediately to the

cash register; the taller man held his gun to

the head of one of the employees and fired, but

somehow missed. The two men then fled the scene

on foot.

In addition to evidence

relating to the Joe's Pizza robbery, the

prosecution introduced a substantial amount of

circumstantial and forensic evidence implicating

Chichester and his alleged accomplice in the

Little Caesars robbery, including evidence that

a shoeprint left on the counter at Little

Caesars matched that of a shoe found in the home

of Chichester's alleged accomplice, and evidence

that Chichester told a friend that he needed to

dispose of a pistol because"he had a body on the

gun."

In response to the

prosecution's evidence, the defense introduced

evidence suggesting that Chichester was in

Washington at his job in the family janitorial

business on the evening of the murder.

Chichester's mother, Vivian Chichester,

testified that she had Chichester pencilled in

on her schedule to work that evening, and

Chichester's sister, Vivian Pina, who was also

scheduled to work that evening, testified that

she frequently worked with Chichester on

weekends. Neither Chichester's mother nor his

sister, however, had any independent

recollection that Chichester actually worked on

the evening of the murder.

Chichester was found guilty

of capital murder, robbery, and firearms charges

on September 20, 1993. On December 2, the trial

judge imposed a sentence of death, based on the

jury's findings of the aggravating factor of

future dangerousness and no mitigating

circumstances.

The Virginia Supreme Court

affirmed the sentence on September 16, 1994, see

Chichester v. Commonwealth , 248 Va. 311 (1994),

and, on February 21, 1995, the United States

Supreme Court denied Chichester's petition for

writ of certiorari , see Chichester v. Virginia, 513 U.S. 1166 (1995). On August

30, 1995, Chichester filed a petition for writ

of habeas corpus in the Virginia Supreme Court.

On November 19, 1996, the petition was dismissed,

and, on January 10, 1997, Chichester's petition for

rehearing was denied. On June 19, 1997, Chichester

filed this petition for writ of habeas corpus in

the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Virginia. The district court

dismissed the petition on April 7, 1998. From

that order of dismissal, Chichester appealed.

II.

Appellant initially raises

two types of claims of ineffective assistance of

counsel. First, appellant asserts that trial

counsel was ineffective for failing to

investigate and present evidence allegedly

suggesting that the man on the customer side of

the counter -- purportedly Chichester -- was not

the "triggerman" in the shooting.

Second, appellant asserts

that trial counsel was ineffective for failing

to impeach the testimony of Jack Burdette, the

only witness to place Chichester at the scene of

the crime. Appellant also contends that the

district court incorrectly denied his motion for

the appointment of experts to assist in the

development of his claim of prejudice resulting

from trial counsel's actions. We address each of

these claims in turn, evaluating appellant's

ineffective assistance claims under the twoprong

standard of Strickland v. Washington , 466 U.S.

668 (1984).

A. Appellant first asserts

that trial counsel was ineffective for failing

to investigate and present various pieces of

evidence allegedly suggesting that Chichester

was not the "triggerman" in the shooting, and

therefore not guilty of capital murder under

Virginia law. See Johnson v. Commonwealth, 220

Va. 146, 149-50 (1979).

We begin by considering

whether it was unreasonable for counsel to fail

to introduce evidence at trial that Chichester

was not the shooter. At trial, counsel relied

heavily on the defense that Chichester was not

involved in the Little Caesars robbery at all,

presenting evidence from Chichester's mother and

sister suggesting that Chichester was at his job

in Washington as a janitor in the family

business on the evening of the murder. See supra

at 4.

In order to present evidence

that Chichester's accomplice, and not Chichester,

was the s hooter, counsel would have had to

acknowledge the possibility that Chichester was

present at the crime scene -- an admission that

would have seriously undermined Chichester's

alibi defense and potentially subjected

Chichester to conviction on all of the non-murder

charges. We therefore agree with the district

court that trial counsel's failure to present

such inconsistent evidence was not unreasonable.

See Mazzell v. Evatt , 88 F.3d 263, 268 (4th

Cir.) (holding that trial counsel's failure to

seek jury instruction that defendant was

accessory to crime, rather than principal, was

not unreasonable because it would have been

inconsistent with trial counsel's strategy to

pursue an alibi defense), cert . denied sub nom

. Mazzell v. Moore , 519 U.S. 1016 (1996).

We next consider whether,

even if trial counsel was not under an

obligation to present evidence at trial that his

client was not the triggerman, counsel

nevertheless should have investigated such

evidence, either in order to test the validity

of the alibi defense or in order to impeach

evidence presented by the Commonwealth at trial.

In Strickland, the Supreme

Court specifically addressed the question of the

scope of trial counsel's duty to investigate:

The reasonableness of counsel's actions may be

determined or substantially influenced by the

defendant's own statements or actions. Counsel's

actions are usually based, quite properly, on

informed strategic choices made by the defendant

and on information supplied by the defendant.

In particular, what

investigation decisions are reasonable depends

critically on such information. For example,

when the facts that support a certain potential

line of defense are generally known to counsel b

ecause of what the defendant has said, the need

for further investigation may be considerably

diminished or eliminated altogether. And when a

defendant has given counsel reason to believe

that pursuing certain investigations would be

fruitless or even harmful, counsel's failure to

pursue those investigations may not later be

challenged as unreasonable.

In short, inquiry

into counsel's conversations with the defendant

may be critical to a proper assessment of

counsel's investigation decisions, just as it

may be critical to a proper assessment of

counsel's other litigation decisions.

Strickland , 466 U.S. at 691;

see also Barnes v. Thompson , 58 F.3d 971,

979-80 (4th Cir. 1995) ("[T]rial counsel. . .

may rely on the truthfulness of his client and

those whom he interviews in deciding how to

pursue his investigation.").

As the Supreme Court suggests,

therefore, we begin our inquiry by examining

what Chichester told trial counsel about his

whereabouts on the evening of the murder.

Chichester did not testify at any stage of the

trial or sentencing proceedings.

Trial counsel,

however, submitted an affidavit, stating as

follows: Chichester and his mother told us that

his mother and sister, Vivian, were the only

witnesses who knew his whereabouts on the night

of the crime and that there were no independent

witnesses who could testify as to alibi. We

relied on this information in our investigation

of the case and presented his mother and sister

as witnesses at trial.

J.A. at 3262 (affidavit of R.

Randolph Willoughby and Bryant A. Webb) (emphasis

added). We read this statement unambiguously to

mean that Chichester and his mother told trial

counsel that Chichester was elsewhere on the

night of the murder and that this could be

confirmed by his mother and sister. To hold that

it was objectively unreasonable for trial

counsel not to fully investigate other possible

defenses under which it would be conceded that

Chichester was at the scene of the crime -- and

indeed a participant in the crime itself --

would contravene the Supreme Court's clear

announcement in Strickland that trial counsel

may rely on information provided by their client

in determining what lines of inquiry to pursue.

Consequently, we conclude that any decision by

trial counsel not to investigate, much less

present, evidence that appellant was not the

triggerman was also reasonable.

Even assuming that counsel

had an obligation to pursue the accomplice

defense notwithstanding appellant's reliance

upon an alibi defense, it was reasonable for

counsel not to pursue, or not to pursue further,

the particular lines of inquiry urged by

appellant. First, appellant asserts that trial

counsel should have located, and presented the

testimony of, William Fruit, the 16-year-old

employee who originally told police that the man

on the employee side of the counter was the

shooter.

However, we conclude that

trial counsel did make reasonable efforts to

locate Fruit, even if they were not under an

obligation to do so. Trial counsel attempted to

find Fruit at the address that had been given to

police at the time of the shooting, but found

that he had apparently moved. J.A. at 3264.

Although Fruit's new address appears to have

been publicly available, id. at 3507, trial

counsel was aware of the fact that the

Commonwealth had subpoenaed Fruit to testify at

the earlier trial of Chichester's alleged

accomplice, but the subpoena had been returned

because Fruit could not be found, id . at 3264.

Further, even if trial counsel had located Fruit,

it seems unlikely that Fruit would have been

willing to testify: Fruit's family appears to

have been reluctant to allow even the

Commonwealth's attorneys to talk to Fruit

because of the understandable emotional trauma

he suffered from the shooting, id. at 3288,

and Fruit, who has since been located, continues

to refuse to talk to appellant's attorneys, id.

at 3508.

Consequently, in view of the difficulty

in locating Fruit and the unlikelihood that

Fruit would have been willing to cooperate even

if located, trial counsel's decision not to

undertake any additional efforts to locate Fruit

was certainly reasonable.

Second, appellant asserts

that trial counsel should have questioned

Patricia Eckert, one of the eyewitnesses to the

murder, about the inconsistency between her

earlier statement to police that the man on the

employee side of the counter was the shooter and

her subsequent statement at trial that she did

not see which man was the shooter. See supra at

3.

Again, however, trial counsel's decision not

to crossexamine Eckert in this fashion was not

unreasonable. As counsel explained, Eckert, in

her testimony, had cast doubt on the testimony

of other witnesses that the shorter of the two

men had jumped over the counter, stating instead

that the two men were of the same height.

J.A. at 3263-64. B ecause

Eckert's direct testimony was actually helpful

to the defense in this regard, trial counsel's

purposeful decision not to try to impeach

Eckert's testimony on cross-examination was

reasonable as a matter of trial strategy.

Third, appellant contends

that trial counsel failed to exploit testimony

by Denise Matney, another of the eyewitnesses,

that the man on the customer side of the counter

was carrying a"box-like" gun. Appellant argues

that this description would fit the 9-millimeter

handgun used in the Joe's Pizza r obbery, but

not the .380-caliber handgun used in the Little

Caesars robbery. As the Commonwealth's

ballistics expert, Julian Mason, testified,

however, a 9-millimeter handgun and a .380-caliber

handgun are "very similar in appearance." J.A.

at 1587.

In view of the absence of any

contrary evidence to suggest that Matney's

description of the gun as "box-like" could not

possibly fit a .380-caliber handgun, trial

counsel's decision not to exploit Matney's

testimony was reasonable. 2

Appellant also argues that

trial counsel was deficient for failing to

retain an expert to clarify that a 9-millimeter

handgun, such as the one used in the Joe's Pizza

r obbery, could not be used to fire a .380-caliber

bullet, such as was used in the Little Caesars

murder. Mason, however, himself testified, and

the Commonwealth later stipulated, that a 9-

millimeter handgun could not be so used. J.A. at

1587, 1592.

Fourth, and finally,

appellant asserts that trial counsel should have

sought and introduced expert evidence to

challenge the testimony of Mason, the

Commonwealth's ballistics expert, and Dr.

Frances Field, the Commonwealth's medical

examiner. Mason testified that the bullet used

in the murder must have been fired from a

distance of more than two to three feet away

because there was no g unpowder residue on the

victim's shirt. Id . at 1588. Field testified

that the bullet entered the victim's body in the

upper left chest and traveled downwards and to

the right. Id . at 1085.

Appellant, however, has made

no showing that contrary expert opinion exists.

In the absence of any such showing, appellant's

argument that trial counsel's failure to seek

and introduce contrary opinion was unreasonable

also lacks merit. 3 B. Appellant next asserts

that trial counsel was ineffective for failing

to impeach the testimony of Jack Burdette, the

only witness to place Chichester at the scene of

the crime.

Appellant advances several grounds on

which Burdette's testimony could have been imp

eached, most notably Burdette's convictions for

various crimes, his alcoholism, and his

incomplete initial statements to the police

about the Little Caesars incident. All of these

grounds for imp eachment, however, were brought

out by the Commonwealth on direct testimony. J.A.

at 9-80 (convictions for various crimes),

1183-84 (alcoholism), 3-95 (incomplete initial

statements). 4

We conclude that trial

counsel's failure to harp on this evidence

during cross-examination was Appellant further

argues that trial counsel should have challenged

Field on cross-examination regarding the fact

that she did not indicate in her coroner's

report whether she had recovered a bullet from

the victim's body or whether she had discovered

any tr aces of gunpowder residue. This claim is

frivolous. Field testified that she had

recovered a bullet and given it to the police,

J.A. at 1085-86, and explicitly stated in her

report that she found no gunpowder residue

around the entrance wound, id . at 3276.

Appellant also offers, as a

ground for imp eachment, the fact that

Burdette's description of the clothing allegedly

worn by the two men differed from that given by

other eyewitnesses. However, trial counsel

extensively questioned Burdette on cross-examination

about the details of his description of the

clothing. J.A. at 1207-09. not unreasonable. See

Hunt v. Nuth , 57 F.3d 1327, 1333 (4th Cir.

1995) (refusing to indulge in a "grading of the

quality of counsel's cross-examination").

C. Finally, in connection

with his ineffective assistance claims,

appellant contends that the district court

incorrectly denied his request for the

appointment of experts to assist in the

development of his claim of prejudice resulting

from trial counsel's actions.

In order to obtain

expert assistance, appellant must show that the

appointment of experts is "reasonably necessary"

for his representation. 21 U.S.C. 848(q)(9). In

making such a showing, appellant must

demonstrate that the appointment of experts is n

ecessary because his habeas petition raises

claims entitling him to a hearing at which such

experts could testify. See Lawson v. Dixon , 3

F.3d 743, 753 (4th Cir. 1993).

Appellant's petition, however,

raises no such claims. Specifically, because

appellant failed to establish that any of trial

counsel's actions were unreasonable, it is

simply unnecessary to determine whether trial

counsel's actions were also prejudicial, much

less to hold a hearing on the matter. See

Strickland, 466 U.S. at 697 ("[T]here is no

reason for a court deciding an ineffective

assistance claim. . . even to address both

components of the inquiry if the defendant makes

an insufficient showing on one."). Consequently,

we conclude that the district court correctly

dismissed appellant's petition without granting

his request for expert assistance.

III.

Appellant next asserts that

the district court should have considered his

procedurally defaulted claims because William

Fruit's pretrial statement that the man on the

employee side of the counter was the shooter

constituted "new evidence" sufficient to sustain

a "gateway" actual innocence claim under Schlup

v. Delo, 513 U.S. 298 (1995). 5 In his brief,

appellant seems to suggest that expert evidence

supporting the argument that appellant was not

the triggerman should also be considered as "new

evidence" for purposes of his actual innocence

claim.

As noted above, however,

appellant nowhere demonstrates that such expert

evidence even exists. See supra at 9. 10

Specifically, appellant challenges the district

court's holding that Fruit's pretrial statement

did not constitute "new evidence" because it was

known to counsel before trial.

Even assuming arguendo that

the district court somehow erred in concluding

that Fruit's pretrial statement was not"new

evidence," we hold that the statement was

insufficient to sustain an actual innocence

claim under Schlup. A substantial claim of

actual innocence is "extremely rare." Id . at

321, 324.

In order to prevail on a "gateway"

claim of actual innocence, "the petitioner must

show that it is more likely than not that no

reasonable juror would have convicted him in

light of the new evidence." Id . at 327; see

also O'Dell v. Netherland , 95 F.3d 1214,

1249-50 (4th Cir. 1996) (discussing application

of Schlup standard), aff'd, 521 U.S. 151 (1997).

We hold that appellant failed

to meet this high standard. At trial, the

prosecution introduced the testimony of two

other eyewitnesses that the man on the customer

side of the counter was the shooter, forensic

evidence further indicating that the man on the

customer side was the shooter, and evidence

indicating that testimony that Chichester said

he needed to dispose of a pistol because "he had

a body on the gun."

Weighing the considerable

body of evidence indicating that the man on the

customer side of the counter was the shooter

against the single pretrial statement of an

underage witness that the man on the employee

side of the counter was the shooter, we conclude

that it was not more likely than not that no

reasonable juror would have convicted appellant

on the basis of the evidence when taken as a

whole. Because the Schlup standard was therefore

not met, we reject appellant's actual innocence

claim.

IV.

Finally, appellant asserts

that the district court improperly admitted

evidence of the Joe's Pizza r obbery, in

violation of his constitutional rights.

Specifically, appellant asserts that the

evidence was admitted in violation of the

Commonwealth's rule of evidence barring the

admission of evidence of prior crimes to show

propensity to commit the crime charged. See ,

e.g., Spencer v. Commonwealth , 240 Va. 78, 89

(1990).

As a threshold matter, we

refuse to consider whether the trial court

erroneously applied Virginia's rule regarding "bad

acts" evidence, because federal habeas relief

simply does not lie for errors of state law. "[I]t

is not the province of a federal habeas court to

reexamine state-court determinations on state-law

questions.

In conducting habeas review, a

federal court is limited to deciding whether a

conviction violated the Constitution, laws, or

treaties of the United States." Estelle v.

McGuire , 502 U.S. 62 , 67-68 (1991).

Our review, therefore, is limited to a

consideration of whether any prejudice from the

admission of the evidence of the Joe's Pizza r

obbery so outweighed its probative value as to

give rise to "circumstances impugning

fundamental fairness or infringing specific

constitutional protections." Grundler v. North

Carolina , 283 F.2d 798, 802 (4th Cir. 1960). 6

We conclude that the Grundler

standard was not met in this case. As the

Virginia Supreme Court noted, the Joe's Pizza r

obbery bore significant similarities to the

Little Caesars robbery: Both robberies occurred

within nine days and in close geographic

proximity to each other; both robbers were

black, one was taller than the other, both were

armed; both robberies appeared to have been

carefully planned to minimize the victims'

opportunity to identify the robbers; both

robbers wore masks and gloves; on each occasion,

the taller man retrieved the spent cartridge

after firing his gun; and in both robberies, the

robbers fled from the scene on foot, rather than

in a vehicle, to minimize the possibility of its

identification.

Further, each r obber

appeared to be familiar with the premises and

the role he was to play in the crimes. In both

instances, the shorter man immediately went

behind the counter to get the money from the

cash register and appeared to know how to gain

immediate access to the areas behind the counter.

Cf . Thompson v. Oklahoma , 487 U.S. 815, 878

(1988) (Scalia, J., dissenting) ("We have never

before held that the excessively inflammatory

character of concededly relevant evidence can

form the basis for a constitutional attack, and

I would decline to do so in this case. If there

is a point at which inflammatoriness so plainly

exceeds evidentiary worth as to violate the

federal Constitution, it has not been reached

here.").

Chichester, 248 Va. at 327.

Having considered the substantial similarities

-- and few differences -- between the two

robberies, we believe that the pattern of the

Joe's Pizza r obbery resembled that of the

Little Caesars robbery so closely as to render

evidence of the earlier robbery highly probative.

Because the significant probative value of the

evidence was not outweighed, much less

sufficiently outweighed, by any prejudice from

its admission, the "fundamental fairness" of

appellant's trial was not compromised. We

therefore reject appellant's claim.

CONCLUSION

Following the dismissal of

his federal habeas corpus petition, Chichester

filed a motion in this court for a certificate

of appealability. See U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2). B

ecause we conclude that Chichester has failed to

make the requisite "substantial showing of the

denial of a constitutional right," id ., we deny

Chichester's motion and dismiss his appeal.

DISMISSED