Dr.

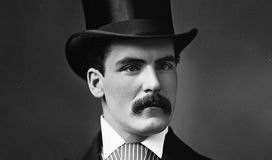

Thomas Neill Cream: Shades of Nightshade

by Joseph Geringer

Batty

"The

mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven."

-- John Milton

Thomas Neill Cream

loved women. There was nothing he loved more than bright-eyed, soft-skinned,

dimple-faced long-tressed, shapely dolls.

They made perfect

guinea pigs.

Perfect victims.

Perfect outlets for

his sexual-homicidal urges.

And he found them as

easy to embrace as uncorking a bottle of strychnine pills, which he

enjoyed handing to them as if it were candy to cure their assorted ills.

To know that they

would die that night - an excruciating death - would help cure his ills,

too, releasing an inner frustration that bottled up inside him like a

volcano. Women, to Cream, were foul creatures who sinned against God,

and he was their executioner, his duty to society to free the world of

gilt angels.

Cream, doctor emeritus,

lived in an age when the world was taking its first step into a free-form

society just a toenail across the border between Victorian restraint, as

tight as a corset string, and a blushing expression of la risqué, half

unbuttoned, giggling and ready to burst forth its unlaced secrets. The

cherubim with innocent blue eyes was slowly becoming more alluring with

the nibs of devil's horns, and, it is believed, Cream loved to see if

they would pop out in his presence. When they did, if they did, then he

had the innate excuse he had been looking for in the first place to kill

them - because, after all, they were the spawns of Lucifer, women were,

and deserved to be slain.

Not to suggest that

the old boy was merely a by-product of his age. Not at all. Victoriana

was a fine age, a splendid time to live, a season for encouraging

record-changing scientific discoveries, altering philosophies, upraising

social consciousness, strengthening national economics, expediting

commerce and penning a new form of literature. But, it was not an age

for someone like Dr. Cream who had enough trouble living under

conservative codes let alone novel ones. He could not understand, for

instance, why Salomé, who danced the seductive dance of the seven veils,

was no longer considered a harridan, but a heroine as glorified by Oscar

Wilde.

He needed to get under

those veils to see what he might find.

Cream was not an

average murderer, says Angus McLaren, who wrote the finely chiseled

Prescription for Murder. "His outrageous crimes were the result of an

individual psychopathology wedded to a generalized misogyny or mistrust

of women at a time when women were making a well-publicized bid for

greater autonomy. The interest of his case accordingly lies not so much

in what it can tell us about him, as in what it reveals about...the

particular sexual and cultural context of late Victorian society, a

society made anxious in the rise to threats of reputation, the increased

number of women in public life, the apparent blight of degeneration and

the erosion of gender boundaries."

From his native Canada

he traveled to the world's Gamorras in search of an answer to the great,

confusing, mystifying, exasperating female mystery. He was uptight,

penned up and strung up, and he destroyed what he just could not

understand. That was his fixation.

"His actions were

probably governed by a mixture of sexual mania and Sadism," writes W.

Teignmouth Shore, who wrote the preface for Trial of Neill Cream for the

"Notable British Trial Series" in 1923. "He may have had a half-crazy

delight in feeling that the lives of the wretched women he slew lay in

his power, that he was the arbiter of their fates...Sensuality, cruelty

and lust of power urged him on. We may picture him walking at night the

dreary, mean streets and byways of Lambeth, seeking for prey, on some of

whom to satisfy his lust, on others to exercise his lust, on others to

satisfy his passion for cruelty..."

His was a Jack the

Ripper mentality - some people believe he was Jack the Ripper - powered

by his own eroticism and confusion.

Suspicions Early On

"No one ever suddenly became depraved."

-- Juvenal

When Thomas Neill

Cream, the doctor who was to poison at least seven female patients in

North America and Great Britain, graduated from Quebec's McGill

University, the subject of the dean's address that year was, "The Evils

of Malpractice in the Medical Profession."

Throughout college,

there seemed to be no forewarning of the devil stirring under his

foppish clothing and dandy manners. Fellow students noticed that Cream

had a chronic interest in chloroform and other drugs that desensitized

patients, but did not regard that as a portent. Chemistry Professor

Louis Craik would later recall that Cream's one surface persona was as a

"fast and extravagant liver". He effected a fondness for money and

delightfully suffered a reputation as a starch-collared, wealthy fop.

However, a number of

particular acquaintances wagered that it was Cream himself who, after

graduation, set fire to his lodgings at 106 Mansfield Street in

Montreal, kindling the place just enough to collect $350 insurance for

charred clothing and a few personal effects that he planned to dispose

of anyway. If Cream was the arsonist, it was a mere transgression

compared to his crimes to come.

Born in Glasgow,

Scotland, on May 27, 1850, he was the first of eight children of William

Cream and Mary (neé Elder). Biographer W. Teignmouth Shore rues the fact

that "as is too often when writing the life of a saint or of a sinner,

the records of (Cream's) childhood are very meager. There is no evidence

procurable as to the surroundings amid which he opened his eyes upon

life or of the circumstances which molded his early years."

The Creams migrated to

the burgeoning frontier of Wolfe's Cove, Quebec, Canada in 1854, where

the father found a job with, and quickly worked his way up as manager of,

one of the province's top shipbuilding and lumber firms, Gilmour &

Company. Years passing, the family's male offspring followed in the

squire's trade and joined him when he started an independent lumber

wholesalery, which prospered. All except Thomas. The latter never

displayed much interest in the business, preferring to spend his hours

with his scholastic books and assorted ponderings. Rumor has it he made

an excellent Sunday school teacher at the Chalmer School. In September,

1872, the oldest son left the Cream Lumber Mill to commence his studies

at the well-reputed McGill University. He wanted to be a doctor.

Following graduation

ceremonies in April, 1876, he was detained by a small vigilante

committee comprised of angry members of the family Brooks, from

Waterford, Quebec, whose teenage daughter and sister, Flora, had been

seduced and abandoned by the young intern. He had paid her several

visits over the last several months, residing at her father's hotel, and

after his latest stay, the girl had become ill. Town physician Dr.

Phelan had examined her to discover she had recently received an

abortion performed by, Flora confessed, medical baccalaureate Thomas

Neill Cream. At the point of the Brooks' moose-hunting shotguns, he was

hustled back to Waterford for an expedient wedding ceremony.

The honeymoon was all

too brief. Flora and her family awoke the morning after to find the

wobbly-kneed groom vanished. But, he left a letter on the pillow beside

her where his head should have been. The best that the prodigal could do

for the bride, read the note, was to promise to keep in touch. It is

doubtful he even took the time to leave a few kisses. Although he did

keep in touch, as we shall see.

He was too busy

scurrying off to London, England, to further his studies abroad. And

London, he heard, would offer opportunities unheard of in the backwoods

of Waterford, Canada.

In the second half of

the nineteenth century, Britain claimed some of the finest medical

schools in the world and expected both genius and ethics from the

physicians they bred. After all, both traits were wanting. London,

Glasgow, Manchester and other large cities in the United Kingdom had

long been bursting across their boundaries, too fast for the country to

keep up. The population blossomed and, adding to it, penniless

immigrants from across Europe wandered to the little island, searching

for an escape from desperate conditions to find nothing better, if not

worse, in the rambling slums of Britain's largest burghs. The conditions

in London's East Side, for instance, were deplorable, an abomination.

Disease spread rapid-fire though sexual contact and other means; it

hatched in the damp rotted floorboards of antique doss houses, and rode

the wings of vermin who infested the clothing that was never washed, and

flowed amid putrid masses in open sewerage. The very air carried old

plagues and unventilated tenements incubated new ones. In the dimmer

sides of London, such as in Spitalsfield or Bluegate Fields, police

reported instances - and these weren't rare - where corpses remained

unburied on their beds in cheap-houses, lying amid a dozen idlers living

in a room designed for no more than five, or toddlers picking bone

scraps from bins beside the curb where a carcass of a dead horse lay,

fly-swarmed.

By the middle of the

century, the nation realized that while the Industrial Age had been

grinding away to improve living conditions, it was losing the battle to

abject poverty. Social Parliament shouted, "Eradicate the slums!" but in

the meantime a stoppage was needed to curb the flow of death-dealing

germs. This meant a sharper corps of doctors. For years, county colleges

had unleashed doctors half-trained or half-eager to combat the flush-up

of disease. According to W.J. Reader, author of Life in Victorian

England, "At the beginning of the century, there were only three bodies

in England - the Royal College of Physicians, the Royal College of

Surgeons, and the Society of Apothecaries - who could claim anything

like a systematic course of medical education, attested by examination.

(But), the 1858 Medical Act...raised the whole standing of the medical

profession by insisting on proper qualifications." Schools dedicated to

the advancement of science and medicine began to appear throughout Great

Britain. Hospitals began weighing the remedial needs of cities like

London and putting those needs under the microscope to shape a

curriculum for their lectures and exams.

Notwithstanding, much

was expected from the foreigner Cream when he registered at St. Thomas'

Hospital, Lambeth, South London, in October of 1876. He required further

training and an apprenticeship before he could apply as surgeon, but the

experience offered at St. Thomas was an excellent start. Within it

passed the likes of Thomas Lister, the antiseptic pioneer, and Florence

Nightingale, who had started a nursing college for women there. After

six months of attending the medical theatres, however, he did not pass

the entrance requirements at the Royal College of Surgeons. Returning to

St. Thomas for extended education, supplementing it with a hands-on

stint as obstetrics clerk, Cream finally applied to the Royal College of

Physicians and Surgeons in Edinburgh, Scotland. This time he was

accepted and earned a license in midwifery.

*****

One of the reasons

Cream may have gotten off to a slow professional start in London was his

preoccupation with wealthy young women. As a fellow of above-average

looks and a promising profession, Cream had little difficulty meeting

the female sex. Feigning to be a bachelor, he spent much time courting

several ladies from the Westminster (West End) society circle with

elegant townhouses, glittering white carriages and many shillings

accruing interest in the Bank Of England on Threadneedle Street. Instead

of diving nose downward into the clinical pages of his textbooks, he

whiffed the perfume tempestuous on the soft, warm throats of his

favorite well-bred ladies.

Victorian London was a

Lothario's paradise; it offered on plates of allure pleasure in many

shapes and forms. Of London, novelist Jane Austen had jocularly written

that she avoided it in fear of temptation, and her appraisal was

justified. Cream, having been raised in the shadows of the pine trees

and lumber mills of Western Canada, and schooled in the narrow halls of

old McGill, must have found London a decadence unto itself. He no doubt

marveled at ceaseless carousing available in its many music halls and

vaudeville theatres; he probably got to know, at least on a nodding

basis, many of the stage performers who tended to live near his

residency across the Thames River in what W. Teignmouth Shore calls a "somewhat

sordid and very depressing portion" of Lambeth. When not escorting one

of his ladies d'elite around Hyde Park or Grosvenor Square, he succumbed

to the more earthy attractions found in the halls of frivolity, drinking

Bass Ale and mouthing along to the most clever and oft-naughty ditties

he'd ever heard.

But, he also must have

been shocked by the ease in which a gentleman in tophat and silk cape

could pick up a street urchin for a night, and for so little tuppence.

After nightfall, they hung along the ramparts of Waterloo Bridge in

droves, selling themselves to passersby on their way in and out of

Central London; the blowsy, bust-exposing illiterate shrill with the

Cockney accent must have titillated the male in him but sickened the

psychoses that told him these type of women are sirens luring a man to

evil, no more than filth.

Judging by what he

would become later - and the terrible crimes he would later commit

against prostitutes -- one can only wonder about his initial reactions

and responses to London's vixens. For the record, evidence points only

to his relations with the ladies of gentler class who spoke like ladies,

acted like ladies and dressed like ladies, posing no threat to the

idyllic virtue of womanhood as upright society - and Thomas Neill Cream

- wished to regard it.

As already stated,

Cream's girlfriends believed him to be unwed. Before he departed for

Edinburgh, he no longer needed to lie. He was single again, his wife

Flora having passed away in Canada in August of 1877. Her death

certificate read: Of consumption.

But, was her death

natural? asks Angus McLaren in his Prescription for Murder. He quotes a

memo from an Inspector Jarvis of Scotland Yard who was to investigate

Cream later. After visiting Flora's attending physician, Dr. Phelan, in

Waterloo, Canada, Jarvis wrote: "Subsequent to the marriage when Mrs.

Cream became ill, he was scarcely able to understand her symptoms and he

asked (her) if she had been taking anything, and she said she had been

taking some medicine her husband sent her. (Phelan) told her not to take

anything except what he himself prescribed and she promised not to do

so, and the symptoms he had not understood gradually passed away. Dr.

Phelan says he never saw any of the medicine Cream had sent his wife,

but he strongly suspected him of foul play."

It must be understood

at this point that the availability of most poisons to the masses was,

before the twentieth century, very much over-the-counter in the English-speaking

world. An 1850 edition of Britain's popular Punch magazine criticized

this ease-of-purchase through a cartoon depicting a small child,

shopping for her mother, asking a pharmacist's clerk for a bottle of

laudanum and a pound and a half of arsenic. Frighteningly, the parody

was not far off. While some forms of poison, such as strychnine, one of

the most lethal, might produce a mild interrogation from the seller, a

doctor or medical student ascribed to a medical college could buy any

pharmaceutical he desired without explanation, as long as the sale was

recorded in a log. It was a matter of form - respect, rather - not to

question such a person.

*****

Nevertheless, Cream

must have buckled down in Edinburgh and kept his mind off both poisons

in pill form and wearing corsets, for he quickly completed his studies

there. Whatever changed his mind in pursuing a medical career in the

United Kingdom - a course he seemed in the midst of following - is not

known, but he returned to Canada in late 1878 to set up practice as

physician and surgeon in the bustling town of London, Ontario.

In the center of this

lumbering and brewery town, he opened an office on Dundas Street, above

Bennett's Clothing Store, and seemed to have done quite well before he

became embroiled in scandal in May, 1879. A patient, Kate Gardener, was

found dead in a woodshed behind the store, reeking of chloroform.

Inquiries made, it was shown that she was pregnant at the time of death

but, unmarried, had gone to the new doctor in town for an abortion.

Cream admitted that, yes, she had called upon him for abortifacients,

but he refused her request. Since chloroform was marketable to the

public, Cream suggested suicide. An inquest didn't buy that; for one,

there was no bottle of chloroform found near the body and the face of

the corpse was badly scratched as if the woman had had the chloroform

forcibly administered. The examining board ruled murder.

Cream avoided

indictment, but his reputation was ruined. Too many turned heads and an

empty waiting room signaled it was time to move on.

In Chicago

"They tell me you are

wicked and I believe them, for I have seen your painted women under the

gas lamps luring the farm boys..." -- Carl Sandburg

Cream found it hard to

believe that the city he walked through after alighting from the train

in August, 1879, had been burned to the ground only eight years earlier.

Chicago was now big and brawny, headstrong with assurance, a gargantuan

of iron and brick. From the sandy shores of Lake Michigan, the city

sprawled westward for miles, bearing with utmost confidence its

experience. The air riveted a try-to-knock-me-down-again and-see-what-happens-to-you

swagger. Mean sometimes, sometimes cruel, but at other times soft and

winsome, even passionate, and steadfast always, Chicago was a

testimonial to the longevity of the melting pot of cultures that, united,

determined to remain in place, never to budge again even if the fires

came straight from hell this time.

But, Chicago's mien

was much, much more than idle cockiness. Its industry boomed. The Union

Stockyards just south of downtown guaranteed it the meatpacking center

of the world. Its geographic position being central-continental and

plunked on the edge of the Great Lakes, ensured it the commercial bulls-eye

of goods traveling from the Atlantic to the western frontier, and back

again. Shipping and railcars converged there, to renew, to overhaul, to

unload and reload before moving westward or eastward, over track or

water, over prairie or mountain, to the other half of the nation that

couldn't exist without Chicago being where it was, and what it was.

"Its population was

soaring from some six-hundred-thousand citizens toward the million it

would achieve in 1890," explains writer Angus McLaren in Prescription

for Murder. "Its reputation for municipal graft, incompetent policing

and working-class radicalism had already won it the title of the 'wickedest

city in the world'.(That quote comes from Mark Thomas Connelly's

shocking exposé of fallen angels in the Midwest entitled The Response to

Prostitution in the Progressive Era.) Cream would play his part in

sustaining this reputation."

Dr. Cream's shingle

appeared on Chicago's main artery, at 434 West Madison, the day after he

passed the state board of health exam. His stay in the city was to be

brief, but memorable, and would tragically involve members of the red-light

district not far from where his office was located.

According to McLaren,

Cream was not in Chicago long before he became suspected by the police

as an abortionist who practiced the trade after regular office hours and

strictly against the morality laws of the 1880s. He was not alone, for

there was money to be made in the endeavor. Certain doctors who lived

near the vice centers would visit female patients wishing an abortion at

their own residence or at an out-of-the-way haven of their choice or

dictated by a go-between "midwife" who took a percentage for her

mediation. Many of the medics performing these operations were,

unfortunately, quacks who botched their jobs, heartlessly leaving the

unfortunate women to bleed to death or to contract illness from unclean

instruments or home-made abortifacients. Cream was not a quack, but,

from what is known of him, he felt little remorse if a patient succumbed.

His view of women had

grown abnormal, and it was deepening. On one hand, he craved them

sensually, sexually. He seemed immersed in their aura, yet perplexed,

yet frightened, yet hateful of them. McLaren points to one source who

bills himself only as "One Who Knew Him," who wrote of Cream: "He

carried pornographic photographs" but spoke of such women in terms "far

from agreeable". Others who shared conversations with Cream would later

relate his aversion to females of low caste; he considered them little

more than cattle made for butchering. Some scholars attribute his mania

to the fact that, when in the company of a fast woman, he may have been

unable to perform without the use of drugs; therefore, intimidated and

reminded of his impotency, he manifested a loathing for anything that

should have but failed to arouse him. Perhaps this was true, for the

same anonymous author quoted above attests, "He was in the habit of

taking pills, which, he said, were compounded of strychnine, morphia and

cocaine and of which the effect, he declared, was aphrodisiac."

To present a

psychological thesis of Thomas Neill Cream might require tomes, and it

is this article's aim to state the facts, not to reflect on his

psychosis. All testimony of Cream at this point tells of a man who was

confused sexually, loved-hated women, and who cared nothing for the

patients who came to him for an abortion beyond the coins they were

willing to jingle for services rendered. To summarize, he most likely

used his experiences in Chicago as an abortionist to mete out his

feelings for the value -- or lack of value - of lives of women outside

his perception of morals and a moralistic sphere of existence.

As an abortionist in

the West Madison neighborhood, Cream employed a series of self-made

midwives whose duty it was to arrange for the illegal operations -

brokers, if you may, between doctor and patient. When summoned by a

client, the midwife rented a room in a particular lodging house to where

all involved parties would converge behind drawn shades for the purpose

of ending the pregnancy. Early in 1880, Cream brushed with the law,

narrowly escaping a jail sentence for an abortion gone wrong. After a

prostitute named Mary Anne Faulkner was found dead in a tenement flat, a

fast-talking lawyer with political connections convinced a jury of

twelve men that Cream's presence on the scene was to save the victim,

after an unschooled midwife had bungled her abortion. The doctor was

found not guilty.

Cream also managed to

evade justice after supplying patient Ellen Stack with anti-pregnancy

pills of his own design. She died, as they were laced with strychnine.

Try as they could, the suspicious police could not directly tie the drug

to their suspect.

But, he finally

blundered in his murder of, surprisingly, not a female but a male

patient. A brief Internet biography of Dr. Cream, written by Stephen P.

Ryder and John A. Piper, tells this story: "When Cream wasn't murdering

women and aborting babies, he took it upon himself to market his own

personal elixir to combat epilepsy, and soon acquired quite a following

by a number of patients who swore by the treatment. One of them, a

railway agent named Daniel Stott, made the mistake of sending his wife

to Cream's office for regular doses of the drug. Julia Stott received

much more from the good doctor than just medicine...and when her husband

finally became suspicious of the affair, Cream decided to add a bit of

strychnine to the medicine. Mr. Stott died June 14, 1881, and had it not

been for a move of great stupidity by (the) killer, Cream would have

gotten off 'Stott' free..."

Worried that the death

might reflect back on him, Cream wrote a letter to the coroner, accusing

the pharmacist who, he claimed, added strychnine to his formula. Since

the pharmacist was a man of exceptional reputation, the district

attorney was wary. The body was exhumed and, as Cream attested, large

doses of the poison were found in the dead man's stomach - but Cream,

not the druggist, was blamed. Hearing of the warrant for his arrest, he

escaped to Canada.

"On July 27 the

readers of the Chicago Tribune were provided with a detailed account of

Pat Garrett's tracking down and shooting in New Mexico of Billy the Kid,"

reports Angus McLaren. "The capture of Cream the same day by the Boone

County sheriff at Bell Riviére, Ontario, was a far more prosaic affair.

Cream put up no struggle and, after being questioned in Windsor, was

returned to Illinois to stand trial for murder."

Mrs. Stott turned

state's evidence to save her own neck and, in November, 1881, the courts

sent Thomas Neill Cream packing to Joliet (Illinois) State Penitentiary

for life.

By crooked means, he

would receive a pardon a decade later. From behind prison walls he would

emerge full of hate, evermore, for womankind.

After all, one had

taken ten years off his life.

Returning to London

"Evil

be thou my Good."

-- John Milton

Prisoner 4374 walked

through Joliet Prison's castellated gate to freedom on July 21, 1891.

His early release was made possible by two things: the intervention of

his brother, Daniel, who pleaded with Illinois politicians for leniency,

and the corruption of the state penal system through which bribery could

be obtained. According to Henri le Caron, a Joliet employee, "Money

could accomplish anything, from the obtaining of luxuries in prison to

the purchase of pardon...Everything connected with the prison

administration was rotten to the core."

Upon release, Cream

journeyed to Canada to thank his brother for his services on his behalf

and to collect a sizeable inheritance ($16,000) left him by the passing

of his father. Some of the money had already been greased to Senator

Fuller and Governor Fifer of Illinois to hasten the doctor's liberty,

but Cream still had plenty with which to start a new life abroad. He had

determined to return to the intriguing atmosphere of London.

In Quebec, Daniel and

his wife were taken aback when Cream appeared at their door; prison life

had etched itself across his face and form and nipped his disposition.

Forty, he looked much older. His once full head of hair had ebbed to the

center of his dome, his skin had weathered, and he wore a chronic glower.

Watery, yellow eyes and a nervous gait indicated signs of drug use. The

once-trimmed mustache grew raggedy. His once agile build had drooped

around the middle. He complained of throbbing headaches. When he talked,

he rattled, and Daniel's wife found him irritating. Most of all, she

could not abide his constant disparaging remarks about women. She could

not wait for him to leave.

He departed Canadian

shores in the middle of September, 1891, on the SS Teutonic arriving in

Liverpool on October 1.

*****

London, despite all

its misgivings, was the queen of the British Empire, and the British

Empire was the queen of the world. During Victoria's reign, London was a

rare moment in time, an ideal of the then-modern city, a mentor, a

trophy. An artist's visualization, a statesman's pride, a decorum of

bearing, London was a magnificent city. Its fog that hung about it

served only to preserve it in a chalk-color of phantasmagoric majesty.

Its physical self was

awesome. Michael Jenner, in London Heritage, describes the city as a "predominantly

Gothic image," which left behind "a vast architectural legacy (that)

coincided neatly with the accession of Queen Victoria in 1837 and became

the hallmark for at least the first fifty years of her reign."

In London - A Social

History, author Roy Porter alludes to a description of the city by

journalist Henry Mayhew after viewing it from a balloon. Wrote Mayhew: "It

was a wonderful sight to behold that vast brick mass of churches and

hospitals, banks and prisons, palaces and workhouses, docks and refuges

for the destitute, parks and squares, and courts and alleys, which make

up London...to take, as it were, an angel's view of that huge town where,

perhaps, there is more virtue and more iniquity, more wealth and more

want, brought together into one dense focus than in any other part of

the earth."

*****

Arriving in London,

Cream stayed at Anderson's Hotel on Fleet Street, but a few days later

moved his belongings to a first-floor-front apartment at 103 Lambeth

Palace Road, South London, in the neighborhood he had lived during his

previous stay in the city, not far from St. Thomas' Hospital. Lambeth

was a triangular patch of run-down public houses, apartment buildings

and meager industry bound on the north by the Thames, and across from it,

Blackfriars and Lambeth roads. Connecting it to the central part of

London, across the river, was the huge Waterloo Bridge. Along Albert

Embankment on the Lambeth side, rose Waterloo Station, from where

thousands of suburban commuters emerged each morning to make their way

on foot across the bridge to their workplace in the city.

"Lambeth's streets

smelled of fish shops, jam factories and hop yards - the smells of the

slum," reads Prescription for Murder by Angus McLaren. "Charles Booth (the

founder of the Salvation Army), who studied the area in 1890s, described

its narrow streets and damp courts as harboring 'poverty, dirt and sin.'

The sidewalks were clogged with swarms of 'dirty and often sore-eyed'

children hovered over by mothers in filthy trailing skirts and shawls...Bread,

margarine and tea had to serve the basis of most meals. Meat sold in

Lambeth Walk on Sunday was not fit for sale on Monday. Milk was

adulterated or, if purchased by the tin, devoid of vitamins...The

parish's overall mortality rate was 27.7 per 1,000 as compared to 19.3

for the rest of the metropolis."

Unemployment was high;

the only institutions inside its borders that hired sizeable staffs were

the Royal Hospital for Children and St. Thomas' Hospital - and these

workers were largely professional who lived elsewhere.

Gaiety never seemed to

lack, however. As mentioned earlier, Lambeth proffered plenty of

amusement, whether in women, spirit or song. Most popular were the

Canterbury, Old Vic, or Gatti's music halls, which drew revelers from

all across London to their gas-lit portals beyond Waterloo Bridge.

In London, Cream found

that the headaches he had been suffering since his confinement in Joliet

were worsening. He had always had slightly crossed eyes, which he never

bothered to correct; but only lately did he notice that his vision had

become somewhat blurred. On October 9, he paid a visit to optician James

Atchison's Fleet Street shop, where Atchison diagnosed his problem as

extreme hypermyopia and recommended spectacles to regulate the imbalance

of his eyes and improve his sight. While his focus clarified, the

headaches did not let up. He began ingesting low-grain morphine, which,

when under its spell, gave his face a clenched look and his eyes a

squint.

*****

Thomas Neill Cream

needed an outlet and his outlet became obvious. Posing as a resident

doctor from St. Thomas and signing his name "Thomas Neill, MD," Cream

back in Lambeth "practically confined his activities, finding there the

victims whose slaughter brought him to the scaffold," asserts W.

Teignmouth Shore in the Trial of Neill Cream. Now with thick-lens

spectacles and a balding head he did not look like the young devil-may-care

charmer he had been more than a decade previously. That, in fact, was

his aim: To take on the mien of a sagacious professor to whom women

would listen - and believe - and trust.

The first unfortunate

person to encounter the city's newest sage was pretty 19-year-old

prostitute Ellen "Nellie" Donworth. The daughter of a laborer, Ellen had

taken to the streets of Lambeth after finding her life as a capper in

the Vauxhall Bottle Factory a drudgery. In 1891, she shared a room near

Commercial Street with army private Ernest Linnell, who didn't seem to

mind her occupation. About six o'clock on the evening of October 13, she

left her abode telling charwoman Annie Clements that she was off to see

a gentleman whom she had recently met.

After the sun set on

London, friend Constance Linfield noticed Ellen and a "topper," the term

for a well-dressed gentleman of the era, emerge arm in arm from an unlit

courtyard behind the Wellington Public House, but paid them little

attention. Not much later, another friend, James Styles spotted Ellen

alone, barely able to stand erect, leaning on a gate on Morpeth Place.

Assuming she was drunk, and perhaps might have fallen (for she seemed to

be in pain), Styles braced her until they reached her lodging house. By

the time he got her to her bed, she was convulsing and grabbing her

abdomen and chest in torment. "That gentleman with whiskers and a tophat

gave me a drink twice out of a bottle with white stuff in it!" she

sobbed.

While Ellen's landlady

and others, including soldier Linnell, remained with her, Styles fetched

an intern named Johnson from nearby Lambeth Medical Institute; by the

time Johnson arrived, Ellen's spasms were so terrible that her company

could not keep her in place as she writhed across the mattress and

gasped for breath. The medic recognized her symptoms immediately as

system poisoning. Police arrived and, on Johnson's orders, removed her

to St. Thomas Hospital. She died in the carriage on the way.

A postmortem two days

later uncovered lethal doses of strychnine in her stomach. Coroner

Thomas Herbert confirmed that her last several hours must have been

spent in agonizing pain.

Angus McLaren's

Prescription for Murder paints a horrid description of the agony

effected by strychnine intake: "The most terrifying aspect...is that

although the convulsions are terrible, you do not lose consciousness; in

fact, the mental faculties are largely unimpaired until death ensues.

You know you are dying. The first symptoms are feelings of apprehension

and terror followed by muscle stiffness, twitching of the face, and

finally tetanic convulsions of the entire body. The body relaxes, and

then the spasms strike again. You have a sense of being suffocated.

Indeed, death is actually caused by anoxia - lack of oxygen due to

contraction of the lungs. All the muscles go rigid and the face and lips

turn blue. Death occurs in one to three hours, the face fixed in a

macabre grin..."

Cream purchased the

tools of his trade - the strychnine and other forms of poison - from

Priest's Chemists, 22 Parliament Street. Because he was a certified

doctor attending a run of lectures at St. Thomas (or so he fabricated)

he had no trouble getting what he wanted. As, by law, he was required to

sign the weekly register of sales, we are able to trace each deadly

order. In retrospect, he prepared well for Ellen Donworth's demise and

others. During the first week of October, for example, he made a

purchase of nux vomica in liquid form (containing two alkaloids, brocine

and strychnine). Around Saturday the 10th, he ordered gelatin capsules

which, when he picked them up on the 13th, he judged to be too large,

and returned them for a box of the smaller "No. 5," or Planter's,

capsules. Donworth, who died October 13, appears to have been killed by

the fluid that he mixed into a drink. His next victim, streetwalker

Matilda Clover, most certainly perished after taking the gelatins.

Twenty-seven-year-old

Clover, brown-eyed, slightly buck-toothed and with a pleasant smile,

lived at 27 Lambeth Road with her two-year-old son, landlords Mr. and

Mrs. Vowles, and a servant girl, Lucy Rose. The boy's father had left

Matilda, forcing her to the streets in order to make her monthly rent as

well as afford an alcoholic habit. To her credit, a week before she was

killed, she had begun visiting a Dr. Graham for her drink infliction. To

calm her recklessness, he had prescribed a sedative, bromide of

potassium.

Much of what occurred

immediately before and during the night of October 20 comes from

eyewitness, Lucy Rose, who gave her testimony at the inquest to come.

Clover left her room after dark that evening; quite chipper, probably,

Lucy figured, to meet a man named Fred - that's all she knew about him.

The only reason she was privy to this piece of information was due to

snooping: While dusting her room the day before she had noticed a note

lying on Miss Clover's bureau that read, to the best of her recollection,

"Meet me outside the

Canterbury at 7:30 if you can come clean and sober.

Do you remember the

night I brought you your boots? You were so drunk that you could not

speak to me. Please bring this paper and envelope with you.

Yours, Fred."

Clover returned home

with a man sometime about 9 p.m.. "There was an oil lamp in the hall

which did not give a very good light," Lucy remembered, but the glow was

solid enough for her to ascertain a tall man in whiskers, wearing a silk

hat and a frock coat with a cape. Leaving the gentleman in her room, she

went out by herself for ale. Later - Lucy was unsure of the time - the

man left alone.

Sometime around 3

a.m., the entire house was roused by Clover's screams. When Lucy and the

Vowles couple entered her quarters, they found her naked, "all of a

twitch" upon her bed. She gagged and started vomiting. Contorted in

agony, grabbing the bed-posts, she was yelling that that Fred had given

her pills that she knew now were poisoned.

Doctors were summoned,

but could do nothing to save her. Matilda Clover died in a paroxysm of

pain at approximately seven in the morning.

Unfortunately, her

death was not officially recorded as murder. Her physician, Dr. Graham,

diagnosed that the woman had succumbed by mixing an excessive amount of

liquor - most likely brandy - with the sedative he had prescribed, a

response that would have, he claimed, produced the same bodily fits she

suffered. In short, he wrote her expiration off as "primarily, delirium

tremens; secondly, syncope."

Had the doctor been

more of a reader of newspapers he might have come across an article

entitled, "The Lambeth Mystery," about Miss Donworth's strange

convulsions a week previously that matched Clover's. In Donworth's

case, the police had rightfully marked it as cold-blooded murder.

Why the authorities

chose not to follow up Clover's dying testimony about the mysterious

Fred and his poison is anyone's guess. Lucy Rose even admitted to them

that Clover confessed she had met a man who promised to give her pills

to prevent venereal disease, and that she now believed that man may have

been Fred. But, not for six months would Matilda Clover be considered

the second victim in what would be a series of similar poisonings in

South London. When Clover's cheap coffin was placed in the ground at

Tooting Cemetery on October 22, neither the Metropolitan Police nor

Scotland Yard anticipated that they had what would be called today a

"serial murderer" on their hands.

Here again, we must

consider the mentality of the times - and its irony. Clover was a

prostitute, and prostitutes in Victorian London died nightly by the

hands of jackals they solicited; that was their life, they lived

dangerously. When they were found dead, many an upright London family

reading about the murders in The London Times, considered such tragedies

a percentage factor. The common Londoner was not without remorse - he

proved that in his sympathy for the street-women mutilated by Jack the

Ripper in Whitechapel in 1888 - but he was without patience when it came

to governmental hypocrisy. Statesmen condemned prostitution, but it

thrived; even after the attention brought to it in the Whitechapel

aberration, it thrived.

"Prostitution seems to

have been a fairly flourishing trade, with clients among the most

respectable," W.J. Reader tells us in Life in Victorian England. "In

London...shops and more or less respectable houses in the Strand and

Haymarket advertised 'beds to let' by day; in the evening, (men of all

classes) might be seen entering and leaving in considerable numbers. In

1882, a select committee of the House of Lords remarked that 'juvenile

prostitution, from an almost incredibly early age, is increasing to an

appalling extent...especially in London.'"

But, the police found

prostitutes a black mark on their beat. The London bobby "devoted

decades to making the lives of such women as difficult as possible" adds

Angus McLaren. "In the 1870s (constables) closed down numerous casinos

and dancing rooms, driving prostitutes into the more dangerous trade on

the streets. In the 1880s the police pursued them into the public

thoroughfares, employing vagrancy laws to arrest those simply suspected

of soliciting."

In November, 1881, a

month after he slew Miss Clover, Dr. Cream -- or as London knew him, Dr.

Neill -- received a telegram from his family asking him to come home for

the final disbursement of his father's property. He made necessary

arrangements for the trip, including establishing a relationship with

refined Laura Sabbatini. He had met her on an excursion to Hertfordshire

and, realizing he was no longer a young man, the strange twist of

personalities that was Thomas Neill Cream decided he wanted a

respectable, pretty wife whom he could show off in society. Before he

left England, he insured himself a place in her heart by funding Laura's

dream enterprise, as a designer of dresses for the West End crowd.

Besides that, he escorted her and her near-deaf mother around London,

treating them to dinner in elegant restaurants and showing them the

finer landmarks.

Kissing her goodbye at

the Liverpool docks, he boarded the SS Sernia on January 7, 1892. He

planned to return to London soon.

A

Beauty, Bane and Blackmail

"Many

might go to heaven with half the labor they go to hell."

-- Ben Jonson

Cream was back in

London within four months. By April 2, he had taken up a suite at

Edward's Hotel in Euston Square, and a week later resumed residency at

his old address of 103 Lambeth Palace Road. It was as if he'd never been

away.

He made immediate

contact with the Sabbatinis at their home in Berkhamstead, Hertfordshire,

pouring out his love for Laura and talking her into an engagement.

Celebrating, they dined out, and over a course of Sundays he even

accompanied his betrothed to church services. Galante to the core, he

played the upstanding, outstanding gentleman of good will and total

beneficence.

That was in the grassy

climes of Hertfordshire. But, in London, he was the night prowler once

again. Roaming Picadilly, he spotted an especially good-looking young

woman with heart-faced shape and come-hither gaze outside St. James

Hall. By her plumage and manner, he recognized her as a streetwalker in

search of a client. Tapping her shoulder, he introduced himself as Dr.

Thomas Neill from America currently practicing at St. Thomas' Hospital.

She was impressed and followed him to the Palace Hotel on Garrick Street,

where they dallied until morning.

Over dinner and a

bottle of burgundy at the hotel, he had learned her name was Lou Harvey,

who lived below Primrose Hill at 55 Townsend Road, St. John's Wood. She

lied. Her real name was Louise Harris and lived at [44] Townsend with an

omnibus conductor named Charley Harvey whose surname she had adopted. A

cautious woman, and brighter than the dollies with whom Cream had played

with thus far, Harvey looked before she leaped, especially when it came

to men like this one who said he came from far-off America; she had been

with enough cads and voyeurs - and high toners, too - to distinguish

the gadabouts from the earnests. Something didn't match up here, she

apprised.

That intuition saved

her life.

When Cream was

indicted for his crimes months later, she would recall her meeting with

him: "He wore gold-rimmed glasses and had very peculiar eyes. As far as

I can remember, he had a dress suit on and a long mackintosh on his arm.

He spoke with a foreign twang (and) asked me if I had ever been in

America. I said no. He had an old-fashioned gold watch with a hair or

silk fob chain and seal. Said he had been in the army."

Before they left the

Palace, she agreed to meet Cream again that evening for a drink and some

theatre at Oxford Music Hall. They arranged a rendezvous for 7:30 p.m.

at the Charing Cross underground railway station, adjacent to the

Embankment. She was surprised, however, when he told her that he would

bring along some pills for her to take in his company. "You are so

beautiful, but your cheeks are too pale," he said. "That's what comes

from living in misty London town. These pills will bring a blush of rose

back into your face, my fallen angel."

His angel had not

fallen so far off the scale that she couldn't smell a rat. She met Cream

at the appointed time, but determined to be careful. The evening proved

quite interesting, as recollected by Harvey: "(I) walked with him to the

Northumberland Public-house, had a glass of wine, and then (we) walked

back to the Embankment where he gave me two capsules. But, not liking

the look of the thing, I pretended to put them in my mouth...And when he

happened to look away, I threw them over the Embankment. He then said he

had to be at St. Thomas' Hospital, left me, and gave me 5 shillings to

go to the Oxford Music Hall, promising to meet me at 11 o'clock. But, he

never came."

Cream had no reason to

show, for at 11 o'clock he most certainly was elsewhere toasting to what

he thought was the whore Lou Harvey's last night on earth. But, she had

been more than lucky; the whore had been smart. Just how smart would not

become evident for some time - when the "ghost" of Lou Harvey would hang

him.

No hangman leered at

Cream yet, though, and he considered himself a clever individual,

erasing strumpets in a way that even Jack the Ripper would have envied.

Cream mused: The Ripper soiled his evening clothes in blood, but he

walked away spotless. The Ripper had to hide in shadows from police

lanterns after every killing, but his method allowed him to put many a

footfall between himself and his victims before the initial sign of foul

play. In fact, he could literally employ his tool of destruction in

broad daylight in the middle of Trafalgar Square had he the mind to do

so. Slip'em the pill, tell'em now they'll feel better, and too-da-loo

m'gal!

But...Master Jack

still bested him, for didn't he kill two doxies in a single night?.

Cream calculated: What prevented him from exacting - even exceeding --

that achievement? All he needed to do was to locate two doves in a

single cage idiotic enough to sample his pills for...whatever reason he

could concoct. Ellen Donworth had swallowed. Matilda Clover had

swallowed. And Lou Harvey had swallowed. All whores.

Imagine...imagine...two trollops in one room - better than Jack the

Ripper who had to leave the warmth of his own fireplace twice!

Two victims stirring

at once. Coughing at once. Twitching at once. Dying at once.

Late on April 11,

1892, Cream followed Alice Marsh and Emma Shrivell, a pair he had just

met loitering in St. George's Circus, off the dreary pavements of

Stamford Street. Outside, a tug boat moaned as it crept down the Thames,

rippling the dark waters, causing a succession of waves to slosh along

the wooden pilings that paralleled Stamford. Ascending the squeaking

steps of Number 118, the trio reached the landing where a hallway led to

the girls' separate rooms. Key inserted, they stepped into Alice's flat,

whiffing a strong surge of gas as she lit the jet beside the door. The

cramped cubicle of a parlor took on a ruddy glow.

Cream grinned. Of

course, they credited the bloke's good humor to his expectations of what

was to come, alone with two young, nubile women - Alice was twenty-one,

Emma was eighteen - in the inviting solitude of the apartment. They

promised to drink with him, perhaps do more with him, then - and this

was why he grinned -- maybe sample one of his cute little pills that he

carried in his polished leather Gladstone bag. The pills, he told them,

prevented "the disease" so rampant and feared among the girls'

profession.

They watched the man

as he set the bag on the divan, so pedantically, a cute topper he, soft-spoken

and even a little bit shy. Alice, in particular, felt sorry for this Dr.

Neill, lonely, just come from America to work at St. Thomas, and still

without friends in the city. They whispered and together decided to give

the poor blighter some feminine fondling tonight.

"But we haf'ta be

quoy'et like mice, so's we don' wyke up the oul' biddy lan'lord' Missus

Vogt downstairs," was Alice's only request. "She thinks we're actresses

in town! Wouldn't she be s'rproised!" And she dropped her blouse to the

floor, revealing a curved torso of white frilly puffs and laces. She

tossed a let's-give-the-doc-a real-show kind of wink to her friend.

The carousing over,

they invited the trooper to partake of some malt beer and canned salmon

that Alice had stored in her pantry. "On one condition, that you let me

reward you with a gift," he answered, unlatching his satchel. "You will

find them more precious than money." He motioned to the Queen's

banknotes he flung on the tabletop beside the opened, foaming brown

bottles of Guinness. "Let me be your personal doctor for the evening."

"Woy not?" Emma

chuckled. "You were a mite good patient of ours a few moments ago!"

Alice howled after her

friend's wit and added, "Ver'ly, wasn't 'e now?"

Dr. Neill, their

friend, threw open his case with the delight of an Irishman uncovering a

leprechaun's pot of gold. The women marveled at the sight of little

bottles tucked into little pockets inside the pouches; square bottles,

rounded bottles, corked bottles, capped bottles, green bottles, and

blue, and black, and white; ceramic bottles and glass bottles. Some had

labels with odd words and strange equations; some were numbered with

tape; others said elixir-this or elixir-that, others were bare. From one

of the latter, Cream spilled six gelatin-covered white pills into his

palm, handing each of the women three. "Take these before retiring," he

told them. "I will give you more next time we meet."

"Are you sure these

work?" Emma asked.

"Oh, you can count on

it," he nodded. "Like nothing you've ever tried before."

It was the bewitching

hour, about 2 a.m., when the doctor left Number 118 Stamford. Outside,

he muttered a ga'evening to the local bobby, Officer Comley, who tapped

his helmet in return. Each man went his separate direction along the

Thames. Inside the home, all was quiet...

...Until about 2:30

a.m. The landlady, Mrs. Charlotte Vogt, awakened, half-conscious of a

whimpering upstairs where her boarders lived. This was soon followed by

groaning, then a terrible rhythm of screams attended by a horrendous

banging noise. Mrs. Vogt stirred her husband and they both scrambled

from bed and fumbled in the dark for their robes.

At the top of the

stairwell the couple found Alice Marsh trembling on the hallway carpet,

her body an amoeba, jerking in spasmodic gestures; her hands grappled at

nothing above her open mouth as if trying to catch air in her fists to

plunge down her gullet. Unable to swallow, she spat up bile. From inside

Emma Shrivell's room, a banging continued. When Mr. Vogt broke in, he

saw the younger girl enduring the same grotesque attacks, threshing in

poses he didn't think the human body capable of. One foot slammed the

wall as she, like her friend, groped for oxygen.

The Vogts fetched a

policeman who, in turn, wired for an emergency wagon, but by the time it

delivered the women to St. Thomas they were dead.

At first ptomaine was

suspected, but that was quickly ruled out. An autopsy uncovered deadly

doses of strychnine in both victims. The murders mirrored that of the "Lambeth

Mystery" girl, Ellen Donworth six months earlier.

Scotland Yard took

note. It believed it had a poisoner wandering the streets of Lambeth.

*****

That Thomas Neill

Cream was an evil man, there is no uncertainty. Cream murdered, and he

enjoyed it, thoroughly enjoyed it. And he didn't stop there. As proof

that his crimes were premeditated, take his blackmailing efforts aimed

at getting rich off his crimes while redirecting their blame to London's

innocent. Don't forget, he had tried the same thing in Chicago when he

had accused an uninvolved druggist for the poisoning of Daniel Stott.

It was to be Cream's

greed that would bring about his eventual downfall. He took his

machinations one step too far, and regretted it.

On the fifth of May,

Deputy Coroner George Percival, in charge of the Shrivell-Marsh murder

inquest, received a strange letter signed by one "William H. Murray".

The handwritten piece subtly pointed to a Dr. Walter Harper of St.

Thomas Hospital as being the killer of the two prostitutes on Stamford

Street. At the same time, Dr. Joseph Harper of Barnstaple opened his

mail to find a letter from this Murray accusing his son, Walter, of the

same double murder. The author of the letter promised that for £156 he

would destroy the evidence he had that conclusively linked Walter to the

deaths.

The Harpers, a father

and son team of surgeons who had an impeccable reputation as two of

London's finest, hurriedly notified the police of the crackpot threat.

The police, not in the least regarding the seriousness of both Murray

letters, informed the accused Harpers not to worry, but to please notify

them if the attempts at extortion continued.

Scotland Yard began

wondering if this Murray might not be the same blackmailer who, under

the pseudonym "A. O'Brien, detective," had written coroner Percival in

October, accusing a popular Member of Parliament as the slayer of Ellen

Donworth. Then, as now, the accused, Frederick Smith, also received a

letter demanding a sum of money (£3,000) to stop him from taking his

information to the Metropolitan Police.

Further investigation

revealed that a phantom, "M. Malone," had tried, through the same form

of arm-bending communication, to rouse £2,500 from two different people

whom he defamed as the murderers of Martha Clover: a Dr. William

Broadbent from Portland Square who practiced at St. Mary's Hospital, and

a high-focus aristocrat, Lord Russell.

The only confusion the

police felt was: Martha Clover wasn't murdered.

Or was she?

Because the

handwriting and the tone of all the letters was curiously similar; the

Yard, in re-examining them, strongly believed that they had been written

by the same man. That being so, why would "M. Malone" regard Clover's

death as anything but natural?

Unless...he knew

better.

Strange Tales

"Just

are the ways of God,

And justifiable to men."

-- John Milton

With the murder of

Alice Marsh and Emma Shrivell, the Metropolitan Police Force, assisted

by Scotland Yard, resurged their hunt for the Lambeth Mystery poisoner.

They studied chemists' records-of-sale for names of known criminals who

may have purchased poisons before and during the target period; they

ransacked lodgings of degenerates with a homicidal past, chiefly those

with a record of drug-taking or woman-bashing.

In the Caledonia Road

apartment of William Slater, a known thug with a gnarled face and a

violent record, constables found nux vomica and morphine; Slater was

promptly arrested. Investigators failed to connect him with either the

Donworth or Marsh/Shrivell murders but, ironically, tied him to another

killing, that of a girlfriend who jilted him, one Annie Bowden.

When suspects failed

to surface in London, Scotland Yard entertained another thought. Because

the murders occurred six months apart - October, 1891, and April, 1892 -

the general belief at the Yard was that the murderer was a sailing man

who killed between ports of call - perhaps a crew member of a cargo ship

that carried medicinal drugs and apparatus to and from the British Isle.

Dr. Cream probably

would have gone on unsuspected had it not been for his own self-trumpeting.

Studies of serial killers since that time have led to the hypothesis

that many of them commit mistakes inwardly hoping to get caught. Valid

or nay, Cream certainly proved to be the master of his own fate.

He had befriended a

burly, good-natured former detective from New York, John Haynes, who

lived over and hung about Armstead's Photographic Studio at 129

Westminster Bridge Road, where he had a profile taken in April, 1892.

The talk of the town at the time was the Stamford Street murders, which

had occurred only a few nights previously, and Haynes and Cream (under

the pseudonym Neill) sparked dialogue on the subject. Haynes, because of

his profession, had an interest in crime and had been following the

strychnine murders closely, or so he thought, for he found his new

friend Dr. Neill's knowledge of the subject extraordinary to his own.

Over supper, the men compared notes and Haynes was very surprised to

hear Cream mention details of the murders - and even the names of two

victims -- that he'd never read. Of the latter, they were a Matilda

Clover and Lou Harvey.

After the meal, the

two men walked through darkening Lambeth, Cream halting at one point to

indicate the flickering transom over the address, 27 Lambeth. "There,

John, see: the front door where they entered the night of October 20,

Clover's final night. Clover, she was an imbecile letting a man she

hardly knew into her house, but then again women of her dirt-cheap class

do not live by brainpower, do they!" Cream snickered. "While she went

out to fetch some porter, the killer obviously prepared his move. He

removed the foil from the gelatin pills, three of them, and put them

back in his vest pocket. When she returned from the tavern, he brought

them out smiling, and announced, 'Here is what I promised you!' Well, he

had told her he was a pill salesman from America and would bring her

some medicine to prevent sexual disease, so she didn't question the

surprise. She reached for them, but he closed them tight in his fist,

saying, 'After we make love, my dear. I am clean, you shan't need them

with me.' So -- they cooed and spooned and, after the romancing was

done, they sat down in her kitchen to enjoy the drink. 'Now, before I

leave, let me watch you take these pills!' he told her. 'Don't bite them,

they are bitter if you do; just swallow them whole with your beer.' He

saw her gulp them down, one at a time. Then, tipping his hat, he told

her he would stop by again the following evening. Of course, he knew

better! Telling her to go to sleep now, he let himself out.."

"Amazing! How do you

know all this?" Haynes wondered.

Cream cajoled. "All...er,

surmise."

"Well, you're quite

the surmiser, sir!" nodded Haynes.

"I know you detectives

don't work that way - no assumptions, only facts. Please forgive the

rambling."

"No, quite interesting.

Don't forget, Neill, facts sprout from assumptions. Pretty much, I

imagine, like a doctor's diagnoses."

"Precisely," Cream

rolled a finger skyward to enunciate. "In fact, that's how I became

interested in the case to begin with, by reading the victims'

post-mortem reports in the British Medical Journal."

"I see. Please, go on,

tell me about this - what was her name? Lois Harvey? I must have missed

her story in the papers, too."

"Lou Harvey," Cream

corrected. "I imagine snipped short off Louisa or Louise. Here's

Waterloo Bridge, let's cross it and I will show you where he gave her

the pills that killed her." He led Haynes over the span of bridge,

explaining how he had met Lou Harvey - but, of course, relating it from

a third-person angle. When they reached the northern shore of the Thames,

he paused under a lantern beside the Embankment parapet immediately

south of Charing Cross Station.

"Here they stood,

right here," Cream posed, "just having finished a sip of the grapes at

the Northumberland. They were supposed to be on their way to the Oxford

for a respite of vaudeville that began at 8:30, but he detained her here

admitting that he must leave her for a while, as rushing business called.

He dropped into her small gloved hand some money for the show, where he

promised to meet her by curtain call, and then two gelatins. 'For your

color!' he told her. The stupid trollop believed him. And she swallowed

them. Well, then he...er, I imagine he scooted after that pretty scene

and left her standing there, at the threshold of hell."

Haynes had been

watching Neill's eyes, glazed and transfixed by his own story-telling. "Where

did she succumb?" the detective asked. "Was she taken ill at the

Oxford?"

"I imagine so. She

couldn't have lived but two or more hours."

"Terrible, terrible,"

Haynes shook his head. "Say, you've left my mouth parched with all your

horror stories, Neill. Where might we imbibe?"

"The Northumberland is

'round the corner this way - come on, I will show you the booth where

the murderer and his lady love sat while they had their last drink

together."

Haynes followed,

observing how this Neill shot from one street to another, maneuvering

about the foggy, night streets of London with more agility than a native,

following the poisoner's steps. As if he knew them by heart.

*****

Haynes' best friend in

London, who had been trying to use his influence to get him a job where

he worked, at Scotland Yard, was Inspector Patrick McIntyre. The day

after his intercourse with Neill, he visited the investigator to spin

his story of an eerie encounter.

"...I tell you, Paddy,

he knew the places, the times, the whole commotion, even their

conversations. Of course, he said he was merely conjecturing, but I

watched his expression when he spoke and...well...I know this sounds

dotty, but, well, I'd swear he was there! Like he'd known them poor

girls intimately. I had the strongest urge to ask him what they looked

like naked," he laughed, "but I was afraid that might be pushing it."

McIntyre, a huge man

behind a huge desk, braced his huge chin on ten arched fingers, pursing

his lips, listening, grimacing under the weight of huge thoughts. He

mumbled, "Clover...Clover...Clover. And Harvey...Lou Harvey." He

unloaded a cumbersome breath and sat back into his huge chair whose

springs screeched as he did so. "I know the name Clover. Her name is

involved with some rum-go who tried to blackmail an acquaintance of hers,

saying he killed her. It seemed odd, because Clover, if it's the same

one we're talking about here, is not considered a victim of foul play.

Her doctor says she died of the drink."

He leaned over his

desk, his chair grinding again, as he sketched a brief note to himself

on a memo pad. "Matilda Clover you say?"

"Mm-hm. And Lou

Harvey's the other one."

"Now her name doesn't

ring a bell at all. I'll check with the coroner to see if such a person

showed up in the morgue. I can tell you one thing, Johnny - where he got

his information is beyond me. There is not nor has there ever been a Lou

Harvey connected with our case, nor in the papers. But -" and he

stretched out in that godawful noisy chair, " - I think she bears

looking into. I'm really glad you came to me."

"At first I thought he

was just a braggart. But, the further along we got on our personal,

little tour of the murder scenes - Donworth's house, the residence of

Alice Marsh and Emma Shrivell, Clover's place and then the spot where

Harvey downed those pills - the more bizarre it became, Paddy. All I

kept thinking is..." He paused. "Need I say it?"

McIntyre shook his

head. "No, I'll say it for you, for I'm wondering the same thing: Neill

might very well be the Lambeth Poisoner."

"Then you think it's

possible?" Haynes asked.

"Johnny, I'm happy my

supervisors didn't hear you say that. I'm trying to get you in here, but

that would have killed your chance."

"Sorry," Haynes rued.

"A good detective knows everything's possible." He saluted a lesson

learned, and stood to leave.

"That's right," winked

the other. "Oh, before you go. Do you happen to know where this Neill

resides? Just in case."

"Yes, on Lambeth

Palace Road. Number 118."

Inspector McIntyre

leaped from his chair and this time the springs actually screamed. "Lambeth

Palace Road, Number 118?"

"Yes. What's wrong?"

"Not a thing. Johnny,

I think you just gave our investigation a boost. That blackmailer of

which I spoke. He had also accused a fellow by the name of Harper for

the killing of the two women on Stamford. Harper lives at Number 118

Lambeth Palace Road, the same lodging house."

"Then you think our

man's Harper?"

"No, I think our man's

Neill."

The Noose

"Be sure your sin will find you out."

-- The Bible

Without him seeing it,

a net was closing in on Dr. Cream. As he had stalked prostitutes in

Lambeth, he was now being tracked by London police, silently. But, the

law was about to climb on his boot heels and not let go until his feet

dangled. It was what Robert Anderson, head of the Central Investigation

Department (C.I.D.), wanted. Exasperated by its longevity, he mandated

the Lambeth Poisoner case to be solved. He wanted results. Results

generated quickly.

Authorities took

several important steps in the wake of John Haynes' interview with

Patrick McIntyre. For one, Scotland Yard discovered through passports

that the suspicious doctor's real name was not Neill, but Cream, and

that he stemmed from Canada. Second, plainclothesmen commenced a round-the-clock

tail on said suspect. Third, morgue records and missing person's files

were dredged and local citizens interviewed for whatever information

anyone could tell the police about the supposed death of someone named

Lou Harvey. Next, the Home Secretary issued an exhumation order for the

corpse of Matilda Clover. Finally, Scotland Yard sent one of its top

investigators, Frederick Jarvis, to North America to research the

personal background of suspect Thomas Neill Cream.

Officer Comley, the

policeman who had exchanged good nights to a topper fitting Cream's

description leaving Alice Marsh and Emma Shrivell's apartment building

the night of the murders, was assigned to the plainclothes unit to

follow Cream closely. He soon reported to his commander, George Harvey

of L Division, that Cream spent many evenings outside the Canterbury

Music Hall,'"watching women very narrowly indeed." After dark on May 12,

Comley, along with Sergeant Alfred Ward, watched Cream buy the services

of a prostitute near the Elephant and Castle, St. George's Road, and

followed them to her home on Elliott's Row. They lingered outside until

he left, but fortunately for the girl, there had been no incident of

violence. Nevertheless, the police were gaining information on Cream's

nocturnal activities, his routes, his habits.

Sergeant Ward sought

out Lucy Rose who had worked as a chambermaid at the apartment where

Matilda Clover had lived, and who remembered seeing "Fred," Clover's

elusive boyfriend whom she brought home that fatal night. Her

description matched that of Cream's.

As is the case with

most professions, prostitutes have an internal network; they know each

other, if not by name, then by appearance, location and reputation.

Victorian London's prostitutes, at a time when Jack the Ripper and Dr.

Cream were killing them, inherently banded together for protection.

After the shocking Stamford Street slayings, Lambeth streetwalkers began

freely communicating with the police.

Two women came forward

with a startling piece of information. Eliza Masters and Lizzie May by

names, they had acquainted Dr. Neill back on October 6 at Ludgate Circus,

permitting him to buy them drinks at King Lud's Castle pub; they chatted

a while, considering him a harmless, friendly chap, and impressed by his

elegant clothing, manner and open pocketbook. Before they parted that

evening, he promised to stop by at their lodging in Lambeth the

following week to treat them to a night on the town. Several days later,

as promised, he contacted Masters at the Oriental Rowhouses on Hercules

Road and told her he was coming to visit. Both women primped and waited,

but he never showed. However, that same afternoon they saw him in the

company of another of their occupation: Matilda Clover.

"Matilda Clover's body

was exhumed on May 6," writes Angus McLaren in Prescription for Murder.

"Fourteen coffins had to be taken out of the paupers' grave before hers

could be removed. Dr. Thomas Stevenson undertook the autopsy. The grave

was dry and the body remarkably well preserved. Stevenson spent three

weeks carrying out the complicated process of shredding the internal

organs, dissolving them in methylated spirit, and boiling, cooling and

filtering the residue. He found that six months after her death, Matilda

Clover's viscera still contained about one-sixteenth of a grain of

strychnine. Probably about as much again had been vomited up. The

residue...appeared purple when color tested. A frog injected with the

fluid found in the corpse's stomach, liver, brain and chest died within

a matter of minutes in the throes of the characteristic symptoms of

strychnine poisoning - tetanic convulsions. The autopsy left no doubt in

Stevenson's mind that Clover had been poisoned."

Last but not least,

revelations from Canada began to roll in, compliments of Inspector

Jarvis. They told of a man, Thomas Neill Cream, whose wife died

mysteriously after he'd sent her pills for her illness; who had been

under suspicion of murder in Ontario; had most assuredly killed

prostitutes in Chicago, and had, through political chicanery, been

released prematurely from prison where he was serving a life sentence

for murdering an intervening man in Illinois.

After obtaining

samples of Dr. Cream's handwriting and comparing them with the extortion

letters that followed each murder, the London constabulary arrested

Cream on June 3, on suspicion of blackmail. They booked him at the Bow

Street Police Station and he was forthwith charged with extortion at the

Magistrate's Court. Incarcerated at Holloway Prison, North London, he

refused to speak but only to exclaim his innocence. Actually the police

had next to nothing to prove his guilt for either extortion or murder --

and he knew it -- but, Anderson, the C.I.D. chief, had manipulated the

arrest as an excuse to detain him in the city in the hopes that the

ongoing investigation would turn up something heady.

During the subsequent

inquest of Martha Clover's death, pieces of damaging testimony indeed

built, built until a solid and frightening picture began to materialize

of Thomas Neill Cream. The inquiry commenced at Vestry Hall, in Tooting

(near the site of her interment), on June 22. Throughout the two-week

hearing, John Haynes detailed his all-too-vivid dialogue with Cream and

the latter's mentioning of Clover as a murder victim before the police

regarded her as such. Elizabeth Masters and Lizzie May told of seeing

Cream in the company of Martha Clover not long before she passed away. A

chemist named Kirby produced a bill of sale for strychnine, which was

signed by Cream. Emily Sleaper, daughter of Cream's landlord, testified

that Cream had told her that he had been following the Lambeth Murder

case and had uncovered evidence to lay the blame on Lord Russell (one of

his blackmail victims). Scotland Yard detective Bennett Tunbridge

related his finding of an envelope in Cream's room bearing scrawled

initials of each of the murder victims in Lambeth, and the dates of

their deaths.

But, Cream sat through

the onslaught relatively unshaken. He was a brilliant man, and he knew

the law. He had written his fiancee telling her not to worry, for the

police had nothing conclusive against him - much hearsay, rumors, that's

all.

Then, the thunderbolt

hit.

Throughout much of the

inquest, Cream sat manacled before the bench, listening without comment

to the proceedings. He kept as physically unmoved as his emotions

remained stolid. At one point late in the hearing, however, during a

break, he happened to glance toward the door of the chamber where an

unusually loud bustle erupted. He saw the lady enter. He blinked. He

blinked again. He whipped off his spectacles, wiped them with his 'kerchief,

and placed them back on the bridge of his nose. And focused. He paled.

He twitched. And his eyes bulged as she walked past him. A bailiff