Burton W. Abbott (February 8, 1928 – March 15, 1957) was a 27 year old University of California at Berkeley accounting student living in Oakland, California who was tried for the rape and murder of 14-year old Stephanie Bryan in November of 1955.

Although the evidence against him was entirely circumstantial, he was convicted and sentenced to death in California's gas chamber. He was executed in March of 1957. As he was being executed, a stay of execution was telephoned to the prison.

The outcome of this case raised questions whether the state has the right to execute a person based on circumstantial evidence alone.

Circumstances

Stephanie Bryan, 14 years old, was last seen on April 28, 1955 on the way home from school taking her usual short cut through the parking lot of the Claremont Hotel. A large-scale search failed to find her.

Then, in July 1955 Georgia Abbott reported that she had found personal effects belonging to the girl, including purse and an ID card, in the basement of the home she shared with her husband, Burton Abbott, and his mother, Elsie Abbott. In interviewing the Abbotts, the police found that Elsie Abbott had found the purse earlier but did not connect it with the case.

Police subsequently dug up Stephanie's glasses, a brassiere and other evidence. No one in the family could account for how the victim's personal effects came to be in the basement. Burton Abbott stated he was driving to the family's cabin 285 miles away when Stephanie disappeared. Two weeks later the victim's body was found in a shallow grave a few hundred feet from the cabin. Shortly after, Abbott was charged with her rape and murder.

Trial

The trial was one of the mostly highly publicized in California history. The prosecution hypotheses was that Abbott had attempted to rape the victim and killed her when she resisted. Abbott pled not guilty.

At the trial all the evidence produced was circumstantial and nothing directly connected Abbott with Stephanie Bryant's death. The prosecution used emotion to overcome the lack of direct evidence by such strategies as showing the jury the rotten clothes from the victim's body and waving her brassiere and panties, making implications he could not prove.

Abbott explained that in May the basement of the house had been used as a polling site with many people having access. Although the prosecution charged attempted rape, the pathologist testified that the body was too decomposed to evaluate it for evidence of sexual assault.

Abbott took the stand and testified for four days, testifying in a calm and poised manner. He spoke in a soft voice and was steadfast in his denials of any knowledge of the crime. He said it was all a "monstrous frame-up". The jury was out seven days before it returned a verdict of guilty of first degree murder. The judge imposed the death sentence.

As provided by California law, there was an automatic appeal to the Supreme Court of California. In detailed opinion describing the facts of the case and reciting the evidence that had been presented at trial, the court affirmed the conviction and sentence of death. See People v. Abbott, 47 Cal. 2d 362, 303 P.2d 730 (1956).

Execution

Abbott was incarcerated at San Quentin to await execution. His lawyers worked to commute his sentence for over a year.

On March 15, 1957, the day of the execution which was scheduled for 11:00 pm, his attorney appealed to the United States Court of Appeals, which was denied, and then tried to contact the governor of California, Goodwin J. Knight, but the governor was at sea on a naval ship and out of reach of the telephone. The attorney arranged with a TV station to broadcast a plea to the governor.

At 9:02 Governor Knight granted one hour's stay by telephone. Within six minutes a writ of habeas corpus was presented to the Supreme Court of California but at 10:42 am the petition was denied. The attorney tried again with an appeal to the Federal District Court but the court refused a further postponement at 10:50 am. At 11:12 am Governor Knight was reached again and agreed to another stay.

At 11:15 am Abbott was led to the gas chamber and strapped in the chair while the governor was contacting the warden by telephone. The executioner pulled the lever three minutes later and 16 pellets of sodium cyanide dropped into the sulfuric acid as Governor Knight reached the prison warden to stay the execution. The warden told him it was too late, and Abbott died at the age of 29 as the governor hung up the telephone.

Significance

This case demonstrates the set of confused legal procedures in place regarding appeals. The federal law allows an attorney 90 days to file for a writ of certiorari after a State Supreme Court's refusal of a rehearing.

However, the State Court set the date for Abbott's execution for two weeks before the 90-day limit. Thus, Abbott was executed with the writ still on file and, therefore, the possibility still existed that Abbott might have won a new trial.

The case also renewed the debate over the death penalty, especially when it is based on circumstantial evidence alone.

Wikipedia.org

Race in the Death House

Time.com

Monday, Mar. 25, 1957

San Francisco Lawyer George T. Davis was in a gut-wracking hurry. He glanced at his wristwatch: 8:50 a.m. In 70 minutes Burton W. Abbott, 29, found guilty of murdering a teen-aged girl, would die in San Quentin's gas chamber. Davis waited tensely for the U.S. Court of Appeals to grant a stay of execution based on his claim that Abbott had not received due process of law. Then the answer came: appeal denied.

Davis moved fast. Perhaps California's Governor Goodwin J. Knight would grant a brief stay. But the governor, who was just preparing to inspect the Navy's aircraft carrier Hancock in San Francisco Bay, was out of reach of the telephone. Davis messaged the ship by Navy radio to turn on a television set for Knight, then arranged with a TV station to broadcast a tape-recorded plea to the governor. Knight got the message. At 9:02 he called Davis by radiotelephone, granted an hour's stay. Six minutes later, Davis presented a writ of habeas corpus to the State Supreme Court. The answer came down at 10:42: petition denied. Attorney Davis tried again, this time with a frantic message to the Federal District Court. Judge Louis E. Goodman refused a further postponement. It was 10:50—ten minutes to go.

"God Bless You." There was just one other chance. Racing into the Supreme Court clerk's office, Davis grabbed a phone, put in another call to Governor Knight, who was sitting in the Hancock's flag plot room and (charged Davis later) "taking tea." Despite the fact that there were two open radiotelephone lines aboard the ship, Davis says he got a busy signal. After arguing futilely with an adamant telephone operator, Davis phoned Knight's Capitol offices for permission to break into one of the lines. At 11:12 Goody Knight came to the phone.

At 11:15 Burton Abbott—a former accounting student who was charged with murder after his wife found the murder victim's purse in the Abbott cellar—was led into the prison gas chamber, still quietly insisting on his innocence. After a minute, Warden Harley O. Teets shook hands with Abbott, murmured "God bless you." Replied the prisoner calmly: "Thank you." A doctor strapped the long tube of a stethoscope to Abbott's chest. Abbott sat quietly, bound to the execution chair. The warden and other officials left the chamber, bolted the door. Three minutes later the executioner pulled a lever, and 16 pellets of sodium cyanide dropped into a crock of sulphuric acid beneath Abbott's chair. The deadly fumes began to rise.

"Has It Started?" In the clerk's office, Davis was talking at last to Governor Knight over the radiotelephone: "There's a new point of law," he said insistently. "There's no time to explain. Can you stop it?" Knight picked up his other phone, spoke to his secretary, Joseph Babich. Knight overheard Babich's conversation as the secretary called the warden on a direct line:

Babich: Has the execution started?

Warden: Yes, sir, it has.

Babich: Can you stop it?

Warden: No, sir, it's too late.

In the death chamber Burton Abbott looked straight ahead, his face impassive. The invisible gas rose. His head inched back, his feet twitched. He died, as on the carrier the governor hung up the phone.

Almost instantly, news of the split-second drama raced across the nation. Loudly Lawyer-Governor Knight explained : "I did everything possible to give Mr. Davis every opportunity to develop anything new in the case. This he could not do. In return he staged a dramatic stunt—with no legal ground to stand on—by waiting until the very last minute and then appealing for still another stay."

Tragedy's Calendar. From Lawyer Davis came the charge that Goody Knight's "open lines" were busy when the governor claimed that they were not. But more important than even the fact that Davis did have an opportunity to make his plea at an earlier date was the clear instance of how a set of confused legal procedures can spell tragedy. On the one hand, said Davis, federal law allows an attorney 90 days to file for a writ of certiorari (a re-examination of the record) upon the State Supreme Court's refusal of a rehearing. But in Abbott's case, the State Court set the date for execution two weeks before the 90-day limit. Thus, with the writ still on file, there was the barest possibility that Convicted Murderer Burton Abbott might have won a new trial.

Elsie Abbott

Mother in Sensational Murder Case Dies at 100 / She never gave up on son's innocence

By Carl Nolte - San Francisco Chronicle

May 02, 2004

To her dying day last Monday, and despite the evidence to the contrary, Elsie Abbott believed her son was murdered by the state of California when he was executed in San Quentin's gas chamber 47 years ago.

Mrs. Abbott was 100 and died at her home on the East Coast.

Her son was Burton Abbott, convicted of the kidnap and murder of Stephanie Bryan, a 14-year-old schoolgirl who disappeared on April 28, 1955, while walking home from school on a Berkeley street near the Claremont Hotel.

It was the beginning of one of the most famous criminal cases in Northern California history, dominating Page One nearly every day for two years.

Elsie Abbott was at the center of it -- a loyal and devoted mother convinced that her son could not possibly be guilty of kidnap and murder. She believed all her life that the real killer was still at large, even theorizing that her own brother had set up her son.

At first, there was a huge search for the missing girl, involving mysterious clues, false leads and even bloodhounds. The largest posse in Bay Area history searched the hills of Contra Costa and Alameda counties.

As it turned out, the worst had happened. Stephanie had been kidnapped and murdered. Her decomposed body was eventually found in a shallow grave near a mountain cabin in distant Trinity County. The cabin belonged to the Abbott family. Stephanie's purse and some of her clothing had been found earlier in Abbott's modest home on San Jose Avenue in Alameda. The evidence was all circumstantial, but everything led to Burton Abbott. He was arrested and tried.

Alameda County District Attorney J. Frank Coakley told the jury that Abbott was "a sexual psychopath" who had dropped clues like "a trail of corn" that led to his arrest. His trial took 47 days, a near record for the times. The jury deliberated 51 hours and 56 minutes. The verdict: guilty. The sentence: death.

The Stephanie Bryan case riveted the Bay Area for nearly two years and drew attention from all over the country; the San Francisco Examiner even hired Earle Stanley Gardner, "the famed detective story writer and well-known crime expert" to offer "his thoughtful comments" on Abbott's trial.

In the days before 24-hour television news and supermarket tabloids, the case was a sensation. "Everybody talked about it; everybody had an opinion," said Keith Walker, a Santa Rosa author who wrote a book on the case.

Abbott, a man The Chronicle called "one of the most perplexing figures in the age-old annals of crime," died in the gas chamber of San Quentin slightly more than 13 months after he was convicted.

Even his last moments took an amazing turn. "There was complete silence" in the gas chamber, wrote The Chronicle's George Draper, who was an eyewitness. "... the silence was broken by the mechanical clank of the device that drops the fatal pellets. Abbott took a deep breath before the pellets dropped and held it as long as he could. The next breath he took killed him."

The emergency phone rang.

Gov. Goodwin Knight had decided to give Abbott a last-minute stay, and his secretary called San Quentin to stop the execution. "He asked whether we had started," said warden Harley Teets. "I said, 'Yes.' He asked whether or not we could stop it. I said, 'No.' "

Burton W. Abbott, a slight man whose last occupation was a student of accounting at UC Berkeley, was 29. The call that would have saved his life was "two minutes too late," said Walker.

Through it all, and for the rest of her life, Elsie Abbott was convinced her son was innocent.

"She thought his execution was legalized murder," said Walker, who interviewed her at length for his book. "She was absolutely, completely 1,000 percent convinced he didn't do it."

For one thing, she believed that the slightly built Abbott, who had tuberculosis and had only half a lung, wasn't strong enough to carry Stephanie's body, much less dig a grave. For another, he had an alibi for his whereabouts the day Stephanie vanished.

He had a wife and a child. "We believe in him," Elsie said of Abbott's family, "because we know him." They called him Bud.

"None of this is real. I can't believe this is happening to me -- to my son," she said on the day his trial began. "He is innocent!" she shouted outside the courtroom on the day he was convicted. "We are never going to stop until we prove that Burton was innocent," she said on the day he died.

After Abbott's death, his wife, Georgia, moved out of California and told neighbors in Alameda that she would change her name. She took the couple's 4- year-old son, Chris, with her. He was not told what happened to his father until years later, when he was a grown man.

Before Abbott died, Elsie bought a newspaper ad offering a reward for evidence of Burton Abbott's innocence. After he died, she gathered up what she said was new evidence that proved Abbott could not have killed Stephanie. She had witnesses, she said, witnesses whose testimony was blocked by the prosecution at the trial.

"She couldn't sleep nights," Walker said. "She was trying to clear his name."

She presented her evidence years later to the Alameda County Grand Jury. The jury would not consider it.

Elsie Abbott even had a theory about the real murderer -- Walker said she was sure it was her own brother, Wilbur Moore, a truck driver who lived in San Leandro. He had set Burton up, Elsie thought, and planted clues that led to an innocent man. The district attorney said "a trail of corn" led to Burton. "Did he leave that trail?" Walker wonders. "Or did someone else leave that trail of corn?"

After years of study, Walker, who is 80 and a former newspaper reporter, has come to the conclusion that Elsie Abbott was right: Her son was innocent. "I don't see how he could have done it," Walker said.

Walker kept track of the family for his 1995 book, "A Trail of Corn." He says Georgia died some time ago; Mark Abbott, who always believed in his brother's innocence, died in 1968. Moore, the truck driver whom Elsie suspected of being the real murderer, is dead, too.

Elsie Abbott, who moved away from her Alameda home in 1983, died Monday at her own home. "She just wore out," Walker said. At the family's request, he will not say where she lived, except it is on the East Coast. She leaves four grandchildren, five great-grandchildren and two great-great-grandchildren.

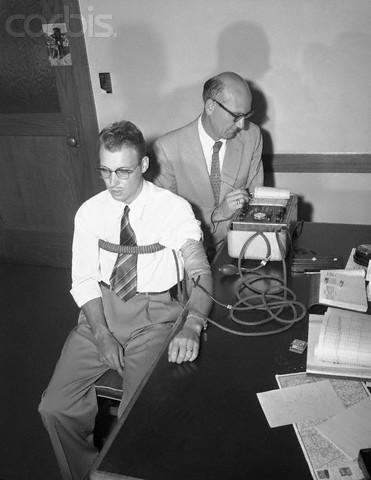

July 19, 1955 - Berkeley, California: Voluntary Test. Burton W. Abbott, (L), shown as he voluntarily submitted to lie detector test today, 7/19, in an effort to prove he knows nothing of the disappearance of Stephanie Bryan. At right, conducting the test is A. E. Riedel, the Bay area's leading polygraph expert. (Bettmann/CORBIS)

Elsie Abbott never gave up on son's innocence